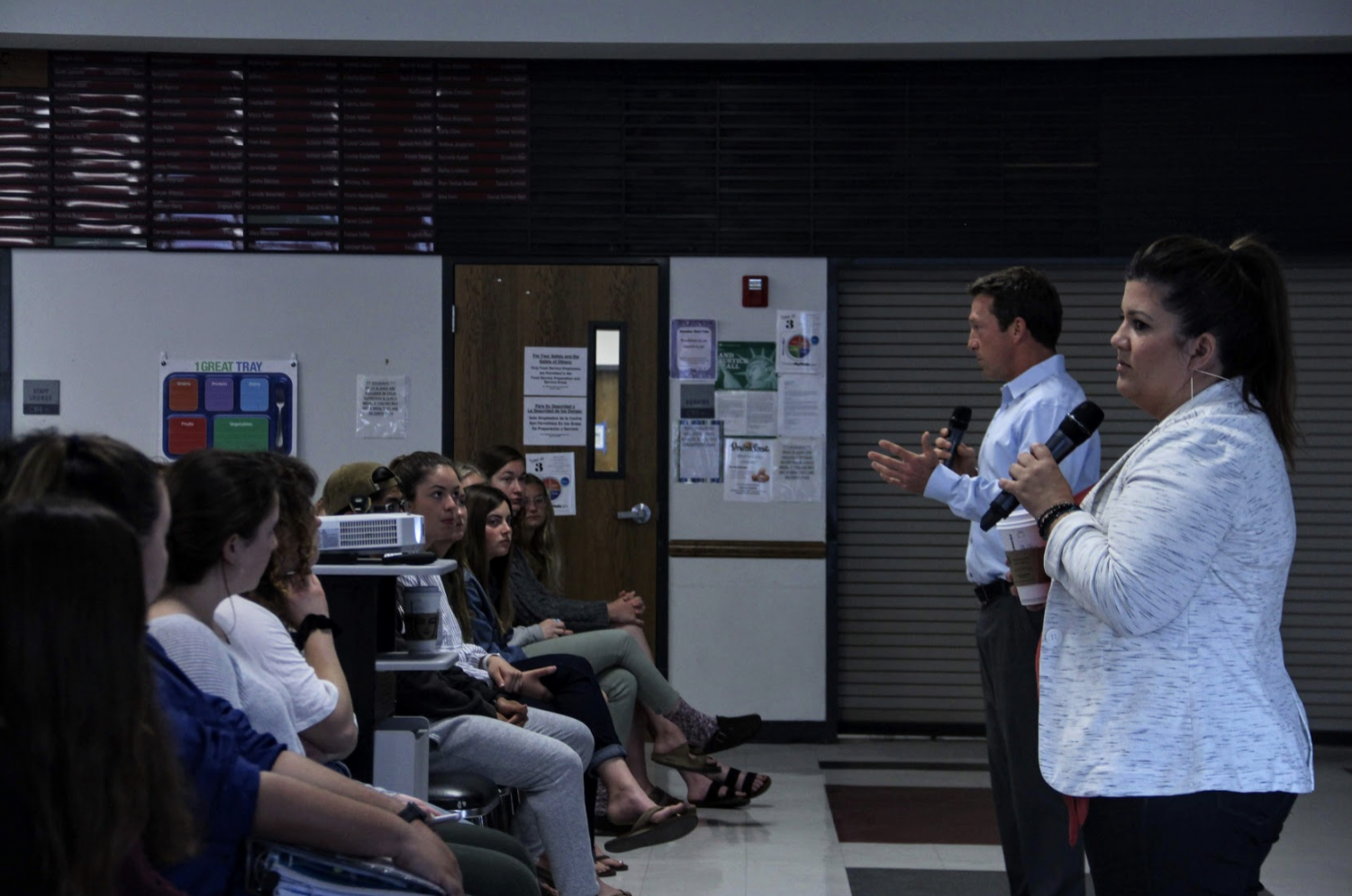

Erin Prewitt and Trevor Quirk illustrate the dangers of intoxicated driving

Erin Prewitt describing the emotional loss with her husband being absent.

April 26, 2019

During the extended second period on April 24, the senior class assembled in Spirito Hall to attend a presentation given by Erin Prewitt, who is the wife of late Chris Prewitt, and her lawyer, Trevor Quirk. In the light of upcoming events like prom and graduation night, Erin Prewitt and Quirk emphasized the dangers of driving under the influence, drawing from the personal experiences of the Prewitt case.

This presentation was a part of Foothill’s Distracted Driving Week, coordinated by Associated Student Body (ASB) Special Events Director Tressa O’Connor. Distracted Driving Week has taken the place of Every 15 Minutes because staff and students felt that it was becoming “less effective,” as O’Connor said.

“Students just weren’t getting the effect of it, and that’s why we decided to switch,” she elaborated.

ASB Coordinator Melanie “Captain” Lindsey seconded this, saying that costliness and lack of impact aided the decision to switch to a week dedicated to distracted driving education.

“Every 15 Minutes costs thousands of dollars to put on, and it’s also extremely taxing emotionally on the staff,” Lindsey said. “When we got through Every 15 Minutes last time we did it, we had a really big meeting afterwards and talked about all of the pluses and deltas of it, like whether it is actually worth it, and the majority of the consensus was that it was not effective enough.”

According to Lindsey, Quirk and Erin Prewitt called and asked if they could do this intoxicated driving presentation.

Erin Prewitt and her lawyer, Trevor Quirk, talking about the evidence they had to go through to “connect the pieces” in her case.

As the crowd settled down into their seats, Quirk started this presentation by asking the seniors a couple of untraditional questions with permission from the school: “Who knows somebody, or even who has [themselves] smoked weed?”; “Who knows somebody, or even who has [themselves] taken Xanax?”; “Smoked weed and taken Xanax at the same time?”

Many students raised their hands, and Quirk used these responses as a segue into the story behind Chris Prewitt’s death. A driver was dually intoxicated with marijuana and Xanax behind the wheel when they fatally hit Chris Prewitt while he was running on the side of the road in 2014.

“April 6, 2014,” Quirk recounted. “6 o’clock in the morning. Chris Prewitt is out for a run—he is training for the Mountains 2 Beach Marathon—and he’s jogging on Victoria, towards the beach. He is about to the Santa Clara River, and a lady [… who] had been smoking blunts […] and taking Xanax and partying all night long, […] passes out at the wheel, […] and hits him and kills him.”

“She actually lodged him into her windshield, and she drove with him in the windshield for over a football field before she stopped,” he continued. “When she got out of the car, she did not call 911—she looked at Chris on the ground as he rolled off of the hood and onto the ground. She looked at him, she went inside of her car, and she got out […] a pipe.”

Quirk showed the seniors the evidence of the case, which included pictures of the driver’s destroyed windshield and the inside of the car. This was used as the “closing argument” given to the court.

Quirk described that Erin Prewitt’s response to this situation was “remarkable” and unexpected for a case like hers: when she came to his office, she asked Quirk if he could help her find a way to “forgive” the driver.

Following a playback of a recording of a witness who was behind the driver when the accident took place, Erin Prewitt made a statement about the accident.

“What happened that morning was, Chris was struck and killed by [the driver] at 6:52 a.m. when he was just a few miles into his 16-mile run, unbeknownst to myself and my daughter,” Erin Prewitt said. “We were back home, and a gentleman knocked on my door about 9 a.m. and I opened the door—I was on the treadmill, attempting to do a little run myself, just not 16 miles—and this gentleman […] asked, ‘Are you Mrs. Prewitt?’”

She then continued to tell the events leading up to the moment when the man, who was the county coroner, told her that her husband had been fatally hit.

“You can’t prepare, right? You can’t prepare for someone who you adore and love [to die],” she said.

She described herself at the moment as “sitting here, trying to make sense that someone killed this really wonderful human.”

”I wanted to just fall apart in that moment,” she continued. “But I had a seven-year-old about 15 feet behind me who didn’t know her dad was dead.”

She detailed that she was able to begin healing emotionally because a good friend of hers offered to take “over the logistics, so I could start falling apart.”

After Erin Prewitt’s account of her husband, Quirk delved into the details behind the trial and his role as the lawyer.

According to Quirk, Erin Prewitt’s initial plan was to reach out to the driver and talk with her in hopes of finding forgiveness. However, the driver was not interested in this concept, which Erin Prewitt called “restorative justice.”

“I wanted to create a contract, and say, ‘How can we give back to our community?’” Erin Prewitt said.

Though the driver did not agree, the judge reduced the sentence for the driver from an anticipated 11 years to the mandatory minimum of 4 years; this number ended up boiling down to 18 months.

On the day of the trial, Quirk says that the driver told the jury that she was not driving intoxicated because she was partying, but rather because “she was at home, and her boyfriend was beating her up.”

“It was so bad that she was actually getting choked out that she peed her pants, and she was fleeing him. She got into her car, forgot that she took Xanax, and the next thing she remembers is waking up and Chris Prewitt’s body rolling off her car.”

Students gather for a special presentation presented by Erin Prewitt and Trevor Quirk.

Though Erin Prewitt believed the driver’s story, Quirk sensed something suspicious. He subpoenaed 30 hours of audio evidence from recorded phone calls that were made during the driver’s time in jail. According to Quirk, the driver was on the phone with a friend and “talking about taking Xanax, smoking weed, doing all of these things she was doing that night, not actually fleeing her boyfriend.”

Since the driver “would never agree” to Erin Prewitt’s wish to use the situation as an educational opportunity for the community, Quirk ended up helping Erin Prewitt settle a lawsuit for 20 million dollars, “the largest wrongful death verdict in Ventura County history.” The money will come from the driver, and another 20 million dollars is owed by the friend who supplied the driver with the narcotics the night of the party.

The goal of the presentation was to educate seniors, especially as large events are coming around the corner and as college is looming, to be responsible and safe when driving.

“It really exposed to me the dangers of distracted driving,” Bryant Nguyen ’19 said. “Because you know, granted, I came in with the knowledge that being a distracted driver, driving under the influence, will have you, is a negative thing and you shouldn’t do it. But, like I said earlier, the impact of having somebody from the other points of view, somebody that has already had it happen to them and their family has really opened my eyes to it.”

“The moral of the story: prom’s coming up, right?” Quirk said. “You guys have weed, it’s so accessible. […] Anybody can get weed. If you’re going to smoke weed, don’t drive your car. It’s real simple. If you’re going to go buy some weed and you give it to your buddy, and your buddy chooses to get high and kills somebody, you better hope that person doesn’t come to me. I’m serious.”

Though Lindsey could not answer what students were supposed to take away from the presentation, she hopes that students learned to be aware of the consequences of intoxicated driving.

“Kids live [… in] their immediate reality, […] and in the teenage brain, the reward outweighs the risk,” she added. “They don’t think about the potential risks of their actions, they think about the reward of their actions. For kids who are drivers, kids who are going to party or kids who are going to participate in some drug use, and then get in a car, they don’t think about just how hugely impactful the repercussions of that decision might be. Sometimes just hearing a truth about somebody that they know might be more impactful than something that they already know is a fake scenario.”