[toggler title=”Trigger Warning” ]The following article discusses a suicide which may be triggering for some readers. Viewer discretion is advised.[/toggler]

As night fades into day on Sunday, May 18, 1980, Ian Curtis is unresponsive in the kitchen of his Macclesfield, Cheshire, England home while a copy of Iggy Pop’s The Idiot spins. Curtis, frontman of English post-punk band Joy Division, struggled with clinical depression and epilepsy. He committed suicide on the eve of Joy Division’s first North American tour at the age of 23.

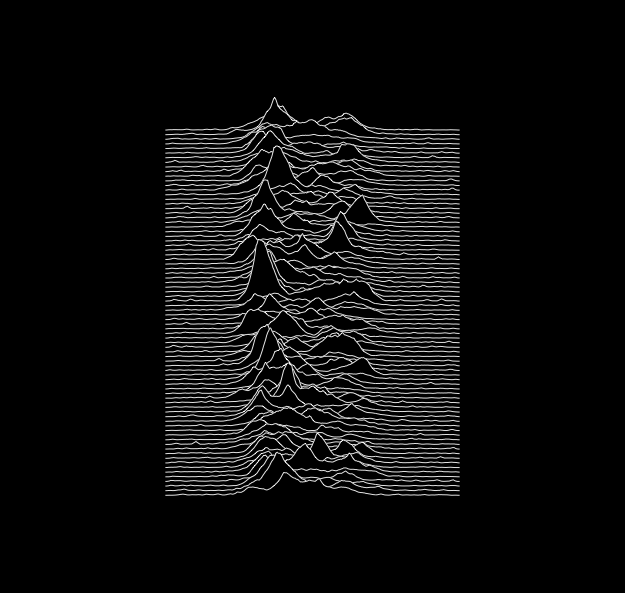

While some may recognize Joy Division from an association with artist Peter Saville’s trippy print depicting the intensity of successive radio pulses (the cover of their 1979 debut record Unknown Pleasures), they should be remembered for much more than that.

In only two albums, the Manchester musicians pioneered the genre of industrial rock and branded a cult-like passion for melancholy in modern music. Curtis’ introspective lyrics atop lively beats managed to give a striking poignancy to the soullessness of drum machines. Using abrasive guitars, choral synthesizers and some background noise, they cultivated a unique, electro-garage sound.

Shortly after Curtis’ death, the three remaining members of the band decided to continue making music together. Opting to ride out the ‘new wave’ of the ‘80’s with the likes of The Psychedelic Furs and The Talking Heads, they further pursued the electronic elements of Joy Division’s music, successfully forming the popular group New Order.

Joy Division’s four-year stint from 1976-1980 encapsulates a creative sweet spot, right after punks realized it was okay to play keyboard and just before the original style they made famous was fractured into subgenres. Curtis’ suicide brought an end to more than just Joy Division’s career – it ended experimental punk as it is remembered today.