When deciding which World War II biopic to see, it’s no contest: “The Imitation Game” stands head and shoulders above its counterpart, “Unbroken.”

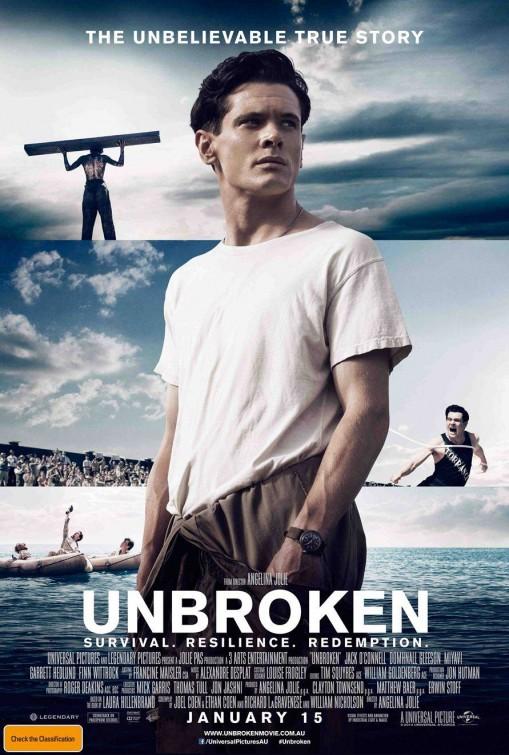

The first of the two, “Unbroken,” follows the remarkable life of Louis Zamperini (Jack O’Connell) as he moves from juvenile delinquent to Olympic track star. When World War II breaks out, he becomes an American bombardier, but, after his plane crashes, he becomes a Japanese prisoner of war. Zamperini endures both physical and psychological torture, but maintains his strength of spirit to carry him through his terrible ordeals.

To be clear, “Unbroken” was by no means a bad movie. It was simply (and disappointingly) too blithely patriotic, too simplistic to stand against the far more complex and layered Alan Turing biopic, “The Imitation Game.”

“Unbroken” just doesn’t address a single flaw of the adult Zamperini, glossing over even his self-professed “naïvete” (after his run at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, he stated his desire to get a photograph with Adolf Hitler, without knowing what kind of monster the dictator was), which is perhaps the biggest flaw the moviemakers could find in his pre-war years.

Without stronger character development, Zamperini simply comes across as yet another milk-drinking GI with no character traits other than that he, as the movie’s title suggests, cannot be broken. Surely Zamperini was a far more nuanced man than the movie makes him out to be, but because the viewer never sees any darkness within him (his rebellious, but rather glossed-over, youth aside), a truly interesting and inspiring man is turned into a caricature suitable for a late 1940s propaganda film, but not for the modern age.

And the unfortunate effect of this whitewashing is to decrease his relatability, and thus the movie’s powerful message. Most humans would experience some sort of despair, however brief, while going through such ordeals as Zamperini did. However, he is perpetually optimistic throughout nearly the whole film, giving no sign of ever thinking, even for a moment, about giving up or giving in. There is little hope that a human could survive Zamperini’s experiences, because the man is not human, but is more than that, elevated above the despairing masses who would react with imperfection if placed in his stead.

Ultimately, the movie gave so little of Zamperini’s relatability that viewers may come away feeling as though they know nothing of Zamperini the man, but have instead watched the careful cultivation of a legend.

Indeed, the barbarous prisoner-of-war camp sergeant Mutsuhrio “The Bird” Wanatabe (Takamasa Ishihara) is a far more realistic character than Zamperini. He is nauseatingly, inhumanely ruthless, but the few perplexing moments of what could be mistaken for humanity serve to brilliantly throw the sadistic monstrosity into sharper relief.

Just saw @MrGrahamMoore‘s @ImitationGame. What beautifully impactful screenwriting! ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ pic.twitter.com/OKeQWqCW4C

— Shane Allen (@shanenews) January 5, 2015

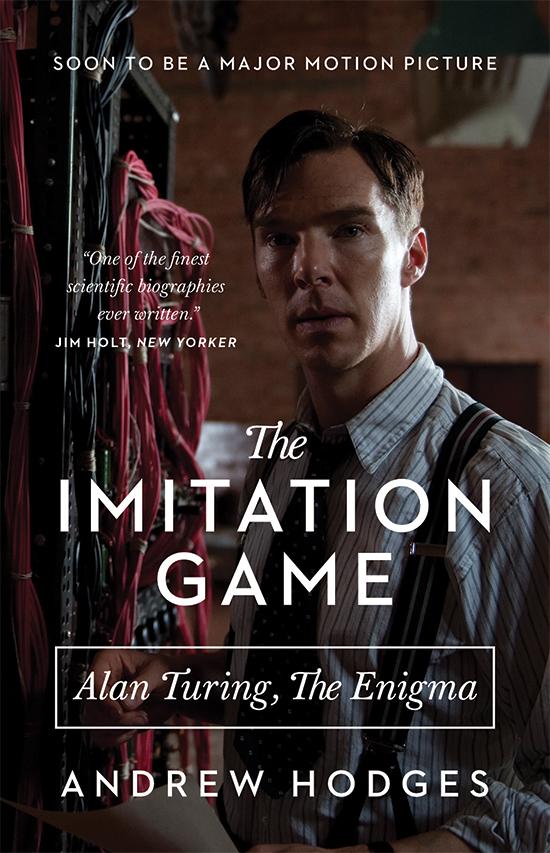

A much more level-headed look at its World War II hero comes with “The Imitation Game.” It follows the brilliant but socially incompetent Alan Turing (Benedict Cumberbatch) in wartime England as he and a team of fellow geniuses attempt to crack the German Enigma code, regarded by many as unbreakable. Turing must manage the team of codebreakers, complex moral dilemmas, and his awareness of his own “black sheep” persona in order to break the code and help win the war.

“The Imitation Game’s” greatest strength comes with its weaknesses, or rather, with its characters’ weaknesses. It does not balk from showing Turing as a genius on the one hand, and an arrogant wretch on the other. It shows fellow mathematician Joan Clarke’s (Keira Knightley) submissiveness to the wishes of her parents and her society, but also shows how she changes blaze a path in what was mistakenly called a “man’s field,” and to realize her own importance in breaking the Enigma code.

Ultimately, this change was what “Unbroken” lacked. Aside from the abrupt change from juvenile delinquent to Olympic track star, Zamperini remains the same optimistic person from beginning to end. In “The Imitation Game,” characters are dynamic, fluid, and unfailingly human.

To be sure, Turing’s biopic is not without its logical flaws. For example, it goes to great lengths to show viewers the difficulty Turing has in deciphering the nuances in conversation, even going so far as to have Turing say himself that he didn’t see the difference between ciphers, in which messages are hidden in plain sight, and regular talking. Yet when he goes to convince Clarke to join the Enigma-cracking team, he can obviously read her social cues. However, this is a minor flaw, and does not detract much from the movie’s overall enjoyability.

As “The Imitation Game” proves, showing the sometimes hazy morality of one’s main character need not make them villainous, nor does it require judging them as either heroes or monsters. It is no disservice to show humans as humans, with their strengths and flaws on full display; indeed, it can even make them stronger heroes, in the end.

Background Photo Credit: nerdlocker.com

Jennifer Holst • Jan 19, 2015 at 9:22 pm

Very nice review and comparison of two films.