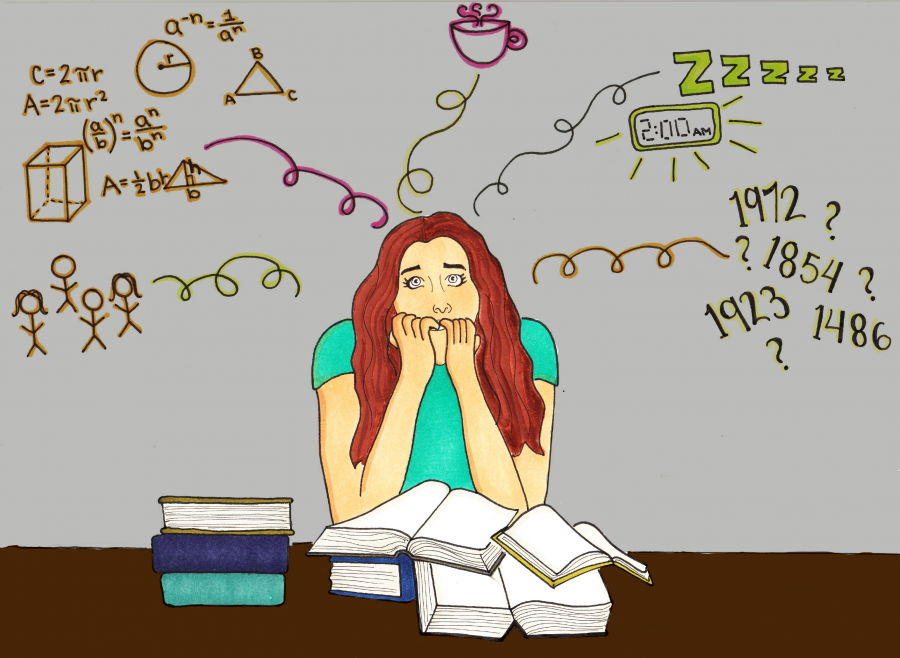

An in-class essay, a history test and a math exam all awaiting you tomorrow, and your anxiety is overwhelming since you haven’t started a minute of preparation. Or, you feel your heart pounding in your chest as you prepare for an important interview. Maybe, you’re driving to school and you notice a car speeding by at the last minute, causing your stomach to turn.

So, what causes you to feel this jolt of anxiety?

To say it simply, this is an effect of stress: the body’s natural response to excessive tension.

When we are stressed, there is a specific sequence of action that occurs in the brain which is reflected by a visible response in the body.

Basically, stress-initiating factors are detected by thought-related regions of the brain—prefrontal cortex, the hippocampus and the amygdala—and a sequence of subcellular interactions occurs within what is known as the HPA axis (hypothalamus, pituitary and adrenal axis).

Now, let’s take a closer look at what really happens.

A hormone known as a mature neuropeptide is secreted by the hypothalamus. This hormone attaches to special corticotropin-releasing hormone receptors in the brain, stimulating the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary gland into the bloodstream.

Along with ACTH, artery-constricting vasopressin is released to raise blood pressure and promote the thyroid gland to increase metabolism, explaining the common symptoms of a fast heartbeat and a change in appetite.

ACTH also influences the outer part of the adrenal gland known as the adrenal cortex, which is responsible for the release of hormones such as cortisol, adrenaline and norepinephrine into the bloodstream.

Adrenaline and norepinephrine are the most common hormones associated with stress since they are responsible for the immediate reactions and for simplifying communications among different parts of the brain.

Adrenaline gives a surge of energy by dilating blood vessels and increasing blood pressure, and norepinephrine directs blood towards areas of higher priority in the situation, such as muscles and the heart, reflected in muscle tension and anxiety that you may experience under stressful circumstances.

Another essential hormone called cortisol serves to make sure that your body has adequate energy for the fight-or-flight response. It promotes brain activity by increasing calcium levels through binds to glucocorticoid receptors in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.

Once the body deems it necessary, cortisol returns to the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland, turns off the HPA system and consequently halts further cortisol production.

As long as you have the appropriate amount of the hormone at normal intervals, stress can motivate you to perform better and be more alert and aware.

However, there’s a huge difference between acute and chronic stress; stress is only healthy if it is short-lived. When the HPA axis is repeatedly activated, it results in excessive cortisol production to the extent where the body may become damaged.

Chronic stress can lead to physical or mental illness and emotional exhaustion. In extreme levels, stress may even be deadly.

As a computer sometimes needs to cool off and repair, the brain needs to do the same. Luckily, there are many simple ways to manage stress. However, if the stress persists and causes harm, see a medical professional as soon as possible.

Some easy ways to deter the effects of stress is to limit caffeine intake, exercise when possible and get enough sleep. Also, it’s great to talk to someone, manage your time and know your limits. Do yourself a favor and spend that extra minute to relax and recharge, because your body—and your brain—will thank you.