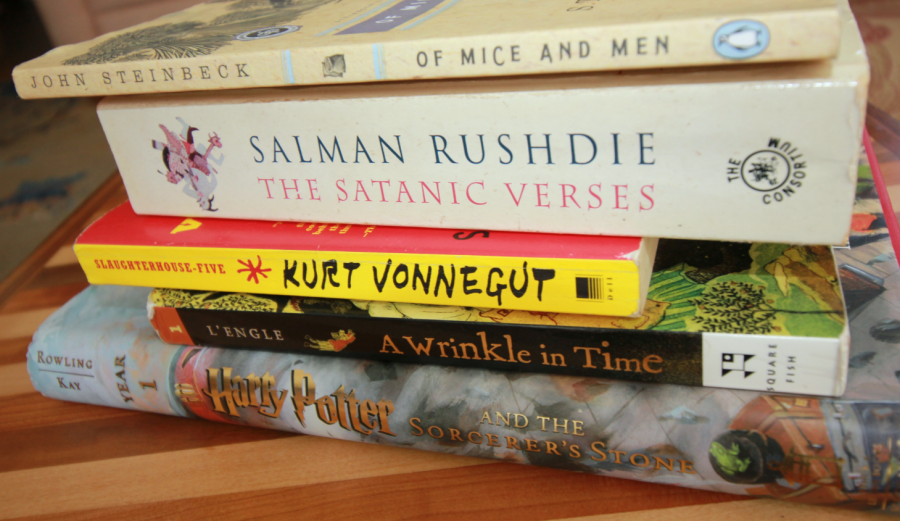

“The Catcher in the Rye,” “Fahrenheit 451,” “To Kill a Mockingbird”: all highly respected novels that have been banned from classroom curriculum at one point or another because of controversial materials that were deemed inappropriate. From Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath” to Rowling’s “Harry Potter” series to Sendak’s “Where the Wild Things Are,” the banning and challenging of books seeps its way into all genres and audiences.

The week of Sept. 24 to Sept. 30 is Banned Books Week, an annual, nationwide celebration of the freedom to read. The movement is run by multiple organizations who work to garner awareness about the detriments that come from censorship of literature. Common grounds for the challenging or banishment of a novel in the past have been the author’s inclusion of explicit language, racial slurs, sexual situations and religious views that are deemed unorthodox.

To get a book approved in the Ventura Unified School District, a teacher must fill out document with a supporting statement on the novel, a dissenting statement on the novel and list possible controversies from the novel. This is then sent to department chairs at other high schools in the district, who consider the novel’s suitability for the teacher’s intended purpose and approve the adoption of the novel. The curriculum specialist at Ventura Unified must then examine the paperwork and write a dissenting or a supporting statement on the novel. Finally, the School Board discusses the novel in session.

English teacher Jennifer Kindred has taught at both public and private schools, which have demonstrated two very different processes for book approval.

In her seven years teaching at a Catholic school, Kindred notes that she had “way more freedom in choosing books than I do here at a public school.” Kindred would talk to the principal, tell them a book she would like to teach, and then the books would be in her classroom in a short amount of time.

Although Kindred is a fan of the efficiency of this quick process, she thinks “there’s something to be said for a [School] Board that looks out for the well-being of all of its constituents” in the manner of approving books for public school curriculum.

“When you’re talking about requiring a whole class to read a certain book, there’s more that goes into it than what I, as a teacher, may want,” Kindred said.

Coincidentally, Foothill literature teacher Melanie “Captain” Lindsey is currently in the process of trying to get two books approved for curriculum in senior English classes: “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood and “Woman at Point Zero” by Nawal El Saadawi.

Lindsey describes “The Handmaid’s Tale” as “a modern satire on the ideas of sex trafficking and slavery,” and “Woman at Point Zero” is about a woman who discovers that she “has more choice as a prostitute than she does as a wife.”

Her goal is to promote inclusion by teaching through the lens of “worldwide female voices.”

“They’re both female authors, and we’re severely lacking. Our curriculum is made up of dead, white authors,” Lindsey said.

As of now, Lindsey thinks “The Handmaid’s Tale” looks as if it is going to get approved because she says that the curriculum specialist, Greg Bayless, is in support of the adoption of the novel. Bayless declined to comment. The book will face the School Board in October.

“Woman at Point Zero,” however, faces more pushback from Ventura Unified for its controversial themes of sex and prostitution.

“We’re not done fighting,” Lindsey said. “What we have in our toolbox is not nearly ethnically inclusive enough, it’s not nearly male/female inclusive enough. It has some major gaps and we want to fill those gaps.”

Lindsey thinks that the major concern that Ventura Unified is facing with “Woman at Point Zero” is that “it has the potential to be taught in the wrong way if it’s in the hands of a teacher who doesn’t really pay attention to the fine details.”

She understands where the pushback is coming from, as if the book was not taught from the appropriate perspective, it could “come across as anti-Muslim” or “anti-male.”

Lindsey and fellow teacher Brooke Schmitt are working on a curriculum guide to be adopted along with the novel to ensure that the novel will be taught in “a culturally, sexually sensitive way.”