As students, we are curious about where the people who teach and mentor us everyday come from. The teachers at Foothill have diverse and unique backgrounds. Some of them are alumni, some are from out of state and a few even come from different countries. These three teachers are not only influential in students’ lives but also give insight to the difficulty of immigration and assimilation, as well as shedding light on cultural differences.

Claire Adams is currently one of Foothill’s social studies teachers who has three separate classes: Health/Geography, Honors World History and U.S. History. Although she professes to love her current job, her call to teach wasn’t always so clear from the beginning.

Born in Hertfordshire, England, Adams first set foot on American soil in September of 1994, attending UCSB as an exchange student when she was 21. It was a shock to her parents to find out her new address at the airport was in Santa Barbara, rather in Berkeley where they believed she would be attending.

“I discovered number one it’s freezing [at Berkeley], and number two they work really hard so I did some more research and decided I wanted to go to Santa Barbara because it wasn’t freezing and they don’t work as hard,” Adams explained her choice wryly.

She majored in American studies while there, but didn’t train as a teacher until as recently as 2005. Before that, she worked in real-estate development, which was “very boring,” according to Adams. During her time at UCSB, she was friends with Justin Frazier, Foothill’s current art teacher.

“The old superintendent, Trudy Arriaga, came to give a presentation at UCSB and she was really awesome so a bunch of us applied to be interviewed here, and at the time there were no art jobs so I got the job,” Adams recalled.

When asked about the cultural differences between United Kingdom (UK) and America, Adams responded in her crisp British accent, “There’s this quote by Oscar Wilde that says, ‘We’re two nations divided by a common language’ and that’s really true.”

The first thing that occurs to her is the food. “I remember going to Subway for the first time and in England you weren’t really given a choice on how you wanted what you wanted your sandwich.”

“If you just ordered a turkey sandwich they’d just give it to you so I remember being overwhelmed by all these questions about what kind of bread I wanted,” Adams said.

Of all the things she misses in England, tea comes to mind first, because “obviously the tea here is pretty dreadful.” She also misses the pubs, which she describes as a kid-friendly, with swings in the back garden and a place for the neighborhood to socialize.

On a more serious note, Adams explained that education in the UK is significantly different from an American education. While the UK is much better in the depth of their studies, she says points can be given to the Americans for the breadth they cover. Additionally, students specialize much quicker in the British school system.

“I dropped all my math, all my sciences, all my languages and I only concentrated on history, geography and English. You specialize much quicker,” Adams explained.

Although her conclusion is that a British education is superior to an American one based off its in-depth studies, she still feels that an American education has its upsides by extending the length of general education.

“Clearly I haven’t spoken a foreign language since I was sixteen and I haven’t done any math since I was sixteen—which if I’ve ever taught you, is very clear as I can’t put anyone into groups,” she said.

With her ability to cross both cultures, Adams has fascinating insight on how Britons view Americans. She feels their attitude stems from a complicated love-hate relationship, an envy of the materialistic culture as well as disdain for American naivety.

“In some ways there’s the money, certainly, and the lifestyle and the quality of life, has always been better than the British quality of life,” Adams reflected.

“We didn’t really get microwaves until the 1980s, and they’ve been around since like the ‘50s here, and just the size of the fridges, and just like massive consumerism,” she continued.

The lure of the American dream seemed to Adams as an amorphous concept that was never really named until she came to the United States.

“British people on the whole have great lives. So I presume the people that are coming here, the Brits coming here, want a better job, want better education or better education for their kids. So I see that the American dream may be a concept that is out there but not really named,” she explained.

In regards to American naivety, she said, “Mr. Prewitt, bless him, used to describe it as ‘America was a teenager and Europe was an adult,’ and America was still going through its growing pains, hadn’t quite decided its path.”

“Whereas I think Europe now would be a very jaded old person who’s like angry and cranky, and maybe America’s getting there but just—I didn’t realize how conservative this country was,” she said.

Adams thinks British people are much more liberal, which she attributes to the fact that the British government is based on socialism and religion is less prevalent in the UK. An example of British liberalism is socialized healthcare.

“You could still go into a hospital and have a baby and not pay a cent, have a heart operation and not pay a cent,” she continued.

Given a choice to move back to England, Adams stated she would prefer to stay in America. Some of her main reasons include feeling disillusioned with post-Brexit England. Furthermore, after so many years in America, there’s an inevitable gap between her two cultures.

“I’ll get into cabs and taxis and they’ll go ‘Oh, you’re American!’ and start blabbering on about why they don’t like Americans,” Adams laughed. Another habit she has picked up from Americans is saying ‘hello’ when walking into stores, which British people, as a general rule, don’t.

“So now when I walk into shops and say ‘hello,’ they all look at me like I’m crazy,” Adams said humorously.

Fortunately for Adams, however, she can decide when “to be American or British, depending on what’s going on.”

-by Becka Shuere

Melanie “Captain” Lindsey is a driving force on Foothill Technology’s campus. She teaches the senior Advanced Placement (AP) Literature and Composition class, is the Associated Student Body (ASB) advisor, chairs the English department and is the Senior Class Advisor. Despite being an integral part of Foothill’s campus and culture, Lindsey has a unique background in comparison to many of her fellow teachers. She was born in Manchester, England and at the age of 9 moved to Sasolburg, South Africa.

Her childhood experiences were shaped by living under Apartheid. Yet, she explains that her experiences while living in South Africa were different than many of those surrounding her.

“I was living in a white only community, in a white only area, in a legally segregated world with parents who were not racist at all,” Lindsey said.

Due to her unique situation growing up, she was more exposed to diversity and culture than many of her peers. She believes that an unwavering respect for other cultures is a central part of her identity. Lindsey recognized something inherently wrong with the country she was living in, even as a child. Looking back, she explains the shortcomings of her education as a child.

“Our education was extremely white-washed. […] The history is written by the winner, they always say, well, that was the whites,” Lindsey said.

“We did a little bit of tribal history, but it was tribal history as it connected to the whites defeating them and taking over their land,” she continued. “You didn’t get to learn the entire history of the country […] You got the white history.”

In contrast with the one-sided viewpoint her schooling gave her, her parents and home life were the opposite. Her mother had many people from the local tribes and blacks working for her that loved and respected her. The men gave Lindsey’s mother the tribal name meaning “mother of peace.” This meant that Lindsey was able to experience the tribal culture and become close with people that had different backgrounds than she would have been exposed to in school. She feels that growing up, she was almost like a sister to the people working for her mother.

Lindsey made a point to learn how to speak Sesotho (the language of the native tribe in her region of South Africa). She thinks that being able to speak to them in their native language was an important sign of respect and appreciation for their culture. They bestowed upon her the tribal name meaning “flower” in Sesotho.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/327943419″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

“When you are given a tribal name, that’s huge. They don’t just give out tribal names, that means that you’ve been accepted,” Lindsey said.

Lindsey is happy for her unique upbringing because it allowed her to see things differently than most around her.

“That’s who I come from, a parentage that have always embraced the differences in others,” she said.

However, as a young adult, she also began to think about leaving her country. She could see that there was so much wrong in South Africa, and she wanted “to be part of the solution, not part of the problem.”

“In South Africa, growing up in a place where you were unsafe if you were anything but white; that was painful to me, and I had no power to do anything because I was an 18-year-old kid,” Lindsey explained.

Lindsey had to leave because of the problems shrouding South Africa following the end of Apartheid.

“You sort of knew where it was [going to] go because the transitions were happening too fast,” she said. “What they really needed to be doing was pouring their resources into educating the younger generations because those were the generations that were going to be able to fix it.”

“Instead, they tried to just flip everything around and so you were asking people who weren’t educated or trained to do jobs they were completely incapable of doing,” Lindsey continued.

At 25 years old, she decided to immigrate to the United States because that was where her, now, husband lived. She had two options, either to ask the American Immigration for a fiance visa or to apply for a spousal visa. She went with the fiance visa because the immigration office (now ICE) looks more favorably on it and it goes much faster. Once the visa was approved, Lindsey had 90 days to get married to her current husband. Then, for two or three years they had to continually go to the immigration office and prove that they had a life together.

“This whole, you just marry someone and get a green card thing they show in the movies is not true at all. I slept on the sidewalk outside the ICE building multiple times. […] If you’re not in line by 4 am, you will not get seen that day,” Lindsey explained.

“You’re not allowed to take any food or drink into the building, […] you get a number if you’re lucky enough, […] and then you sit and you wait. […] So you could be sitting there four, five six hours with no food, no water and no company,” she continued.

Lindsey experienced culture shock when she came to the United States. Entering a new way of life was difficult, and it still can be for her. The differences, even small ones, were difficult to adjust to.

“I remember trying to plan a wedding and a first Christmas with my husband and it’s when those things happen that you realize the differences, even though they’re small differences, […] it was very big. American culture is very big, excessive, or it felt like that to me,” Lindsey described.

“Not being able to use my words for things without people snickering,” she described as one of the most difficult things about immigrating.

“The teasing is the hardest part, the teasing is tough, that’s why I don’t speak so much with an accent anymore because the teasing was so relentless in the beginning that it was hard to take,” she said.

The culture in South Africa is unique and special for Lindsey.

“It’s a lot more religious celebratory and those celebrations are really big. The one I really miss is Boxing Day, which is the day after Christmas,” she said. “Christmas was the day that you spent with your family, […] and then Boxing Day was the day that all the friends got together.”

-by Emma Kolesnik

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Lindsey moved to Sasolburg at the age of 6. She moved at the age of nine. This correction was made at 9:03 a.m. on June 16.

A man known for his quirky giggle, tight-sleeved t-shirts and off-key singing, Adrian Sanchez has provided Foothill with yet another great teacher and provided students with another friend.

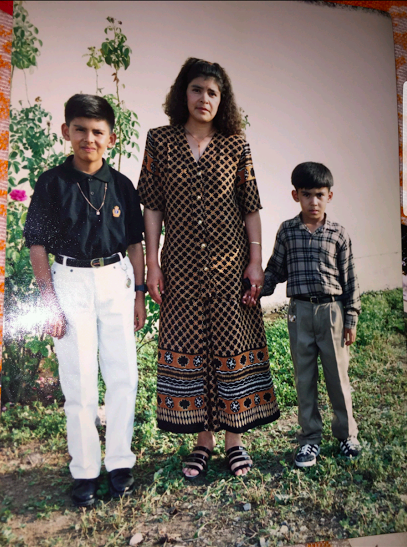

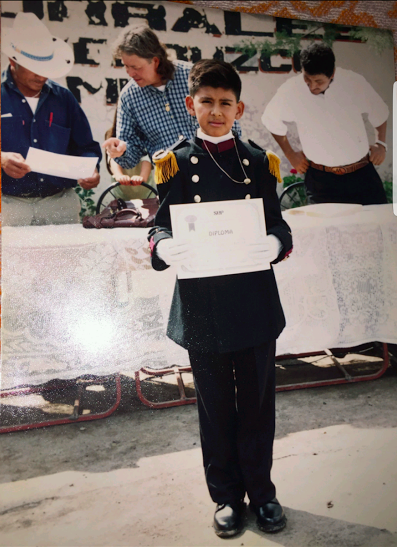

One of three Spanish teachers at Foothill, Sanchez is the only one who can claim to be a native speaker. Sanchez immigrated from a small town in Michoacan, Mexico, known as Pastor Ortiz, to the United States as a 12-year-old in 1998.

“My dad was already working here, living in the U.S.,” Sanchez said. “He made the application so that we could come legally to the U.S., and one day he decided that he wanted to bring the whole family.”

The Sanchez family moved to Reedley, California, in the Fresno area, where they had to quickly adapt to the American lifestyle.

While Sanchez enjoyed the Mexican culture, there was one specific reason that his father uprooted the family and transitioned them to a new life: like many immigrant parents, Sanchez’s father wanted to give his family a better future, especially his three sons.

“There was lack of work in Mexico and we couldn’t survive, basically,” Sanchez said.

Sanchez felt that the language barrier was the largest cultural difference that impacted his immigration. “I spoke no English whatsoever,” he said.

And while even the average English-speaking American teens may find it hard to socially connect at times, imagine coming to a new country and a new school, filled with self-conscious and often brutally-rude middle schoolers, while not speaking a lick of their language.

“Making friends and meeting people, it was very difficult,” Sanchez said.

The American culture itself also offered its fair share of nuances, that Sanchez caught onto “right from the beginning.”

Sanchez described Mexico’s “collective culture” and the sociality that comes with it. “It’s very easy for you to go up someone and just say hi to them, even if you don’t really know them,” he continued.

In what he called an “individualistic culture,” it’s easy to see why America might not be the most friendly country to arrive in.

“Everybody kind of minds their own business and does their own thing,” Sanchez said.

However, people weren’t even what gave Sanchez his greatest struggle; it was academics. “Imagine going to another country with a whole new language, a whole new educational system,” he said.

Understandably, it was painstakingly difficult to try and figure out what the teachers were trying to teach him, and then retain the material and learn it like everybody else.

“It takes a couple of years to kind of understand what other people are saying in any language, so my comprehension was okay, enough to perform,” Sanchez continued.

Keeping in mind that he started speaking English as a seventh grader, in high school his “ninth grade would be [his] third grade.” He said that his understanding of the language allowed him to do the tasks that were asked of him.

“Was it the best work? No. But then again, most of my teachers were not checking my homework, so I was getting all the credit, and because I was doing all the work and getting all the credit, I was getting good grades. However, I was not able to produce and teach that stuff to someone else,” he continued.

Sanchez explained that it took until about the end of his senior year in high school for him to be able to have higher level conversations in English.

“Six years it took for me to somewhat communicate,” he added.

He finally had to latch on hard to the English language when he went to the University of California Davis. “We had discussions and it was nerve-racking and that was when I realized that I really needed to practice,” Sanchez explained.

Sanchez originally majored in sociology, but he changed it to psychology, with a major in Spanish as well. Once he received his Bachelor’s degree, he got his teaching degree at University of California Santa Barbara. He then returned to the Fresno area and looked for jobs around the vicinity because of how close it would be to all of his family.

“I started teaching as a sub while I was waiting for interviews for a permanent position in a school,” Sanchez explained.

He then got an unexpected call from Foothill Principal Joe Bova, which was especially strange considering it was a school that Sanchez didn’t even apply to.

After a previous Spanish teacher had to leave the school, Foothill “informed themselves on available teachers by calling UCSB, who recommended me. My plan was not to move to Ventura. I [didn’t] have family here. But it was great job offer and I had to take it,” he commented.

Most of his relatives, including his parents and brothers, still live in Reedley. Some of his cousins live in that area as well, while one of his cousins lives with him. His oldest brother is 26, the younger brother is only 17, and with a chuckle, Sanchez said, “My parents waited a long time to have that one.”

Even if money weren’t an object, Sanchez would not want to go back and permanently live in Mexico.

“I would obviously go back and visit and perhaps when I retire, it’s something I would consider,” Sanchez said. “But as of now, the U.S. is my country and I like it. I’ve lived here for more than half of my life, now.”

“I’ve already [gotten] used to this lifestyle, I’ve already [gotten] used to this culture, and I’ve [gotten] used to how things work. This is my home,” he concluded.

And it’s a good thing he’s planning on staying, because Foothill will gladly embrace his teaching skills and his personality for now and years to come.

-by Jack Vielbig

Jack Herer • Jun 26, 2017 at 12:56 am

All of these “immigrants” immigrated here legally, so the message is certainly unrelated to what it was attempting to argue against.