“Life’s too short to waste your time writing

about things you’re not interested in.”

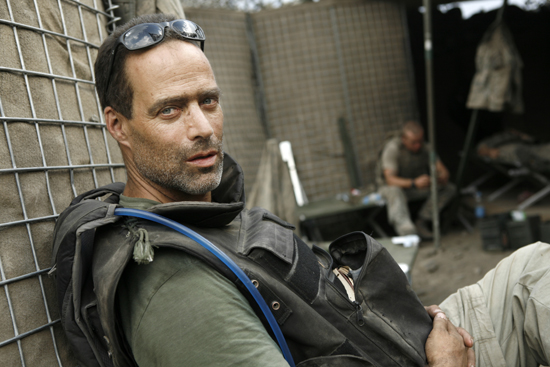

Insightful words for any aspiring writer or journalist, and words spoken by one of the most respected writers in the game, Sebastian Junger.

Best known for his 1997 book “A Perfect Storm” and for co-directing this year’s Academy Award-nominated documentary “Restrepo,” Junger spoke by telephone March 11 with the Dragon Press about journalism, revolutions, WikiLeaks and his next assignment: Libya.

His emphasis in this interview on following your dreams and seeing them through to completion communicated an untiring work ethic for his craft, one in which he puts every ounce of energy necessary to create the best piece.

Q: How did your experiences and perceptions in Afghanistan, as a writer, differ from those of photographer Tim Hetherington?

A: He sees things in a visual way that I’m not trained in. I remember there was one time when everyone was asleep, it was a very hot, boring day, and that was the epitome of nothing going on. And he was creeping around the outpost (OP Restrepo) photographing the sleeping soldiers, and he said to me ‘You know, you never see soldiers asleep. You never get that perspective. This is awesome.’ And I realized that there’s never nothing going on. And it took a visual person to notice that, and as a result of that I wrote a paragraph about what it’s like to be at an outpost where everyone’s asleep in my book (“War”). And I’m sure I saw some things in ways he didn’t…I mean I was really interested in courage, and how courage works, sort of at the neurochemical level, on up to socially, and I don’t think that had occurred to him. That’s a conceptual thing, that’s something that a ‘word guy’ would probably think of. And I think we worked together really well, it was a nice arrangement.

{sidebar id=3}

Q: Were there any changes in the soldiers that you witnessed over the months that you were there that surprised you or that you didn’t expect?

A: They (the soldiers) got pretty bored in the winter, and that created a lot of conflict within the group, they were just adapted to fighting. And then when there was no fighting, it was sort of hard on them. And they all got very edgy before they went home, in the last week there was very little fighting, and they were all extremely jumpy. There was lot of tension in the outpost in the weeks before they left.

Q: How many of the soldiers do you think were able to cope with the sudden transition to civilian life, versus those who are still affected by it today?

A: Well, most of them are still in the Army, doing deployments, and fighting. So it’s hard to know how they adjusted because their not {sidebar id=2}civilians yet. But, Brendan O’Bryne got out, and he adjusted, but it took him awhile, but he had a lot of issues before he even went into the army. So it’s hard to pull those things apart… He was shot by his dad during an argument before he joined the Army, so are his problems a result of that or a result of combat? Who knows.

Q: As a journalist, where do you draw the line between telling a compelling, interesting story and revealing too much about the soldiers or the events you saw?

A: Well, if it’s something that’s going to affect someone’s personal life, I consult with them in the same way I would appreciate being consulted with if someone was writing about me. You know, with Brendan I knew the story about his dad because I overheard him saying it to somebody else. And we all have a sense of ethics and morality, and I just applied those to the situation, and I just thought I should ask him… And no piece of journalism is worth destroying somebody’s private life, unless it’s an issue of national concern. With Brendan’s issue, there wasn’t an issue of “national concern” (laughs). I mean if he had killed civilians in Afghanistan and covered it up, then I wouldn’t really care about their personal life, it would be an overriding issue. So I guess anything I thought was gonna be disruptive to their lives personally, I just checked with them.

Q: Did you see any conduct by the soldiers in Afghanistan that you thought was perhaps unethical orsomehow wrong, i.e. in how they became used to the day in and day out violence? And if you’ve seen the video called “Collateral Murder,” released by WikiLeaks back in November 2010, I was wondering what your reaction to the events that took place in that video were?

A: Yeah, they’re kind of like cops. But I didn’t see anything that I thought violated the Rules of Engagement (ROE). And you know one of the things about that WikiLeaks incident is that WikiLeaks doesn’t mention that those journalists were standing with, and I think I’m correct on this, armed insurgents. That’s not really discussed in the WikiLeaks discussion about the video. That fact that that’s not discussed is an important fact. If I walk into Grand Central with a gun and I get shot, the fact that I’m a civilian is irrelevant… That’s an extremely important detail in the discussion of whether those Apache pilots were right or wrong, that’s just crucial, and WikiLeaks didn’t bring that up, which I think is to their discredit.

Q: Did you and Tim go to the Korengal with the intention of creating a documentary, or did it develop after you went there?

A: I wanted to make a documentary starting in 2005, but I didn’t know how to go about doing that. Tim came onto the project in September 2007, but I was already shooting video in June 2007 on my first trip. And when Tim got there, he realized it was a pretty amazing topic, and I realized that now with Tim I actually had a realistic way of doing this. And things sort of gathered steam from there.

Q: How do you think all of the recent revolutions in the Middle East will change the face of US foreign relations in the region?

A: I think it’s like the Berlin Wall, we have a certain, at least theoretical, support for democracy, but there’s also real concerns about Israeli security… and our own issues with access to oil… and we’ve got our own things domestically to juggle. I think the State Dept. is still figuring it out. And I think one thing’s for sure, the world map is really changing, and like with the Berlin Wall, it’s gonna be 10 or 20 years before our foreign policy has readjusted and found a comfortable place.

Q: Why do you think the revolution in Egypt was so peaceful versus the one in Libya being so violent?

A: The regime in Egypt and the army decided that they weren’t going to fire on civilians… This is violent in Libya because Gadhafi chose to be violent and Mubarak chose not to be violent. I don’t think it reflects the crowd so much as the person that was overthrown. {sidebar id=4} I think Mubarak found a graceful way out and a place to go, and I think that’s hard for Gadhafi. You know, he arranged for the bombing of a passenger plane over Lockerbie, Scotland, and killed some 300 civilians. He obviously has a readiness to use violence. Mubarak, whatever his things in Egypt are, they don’t include bombing civilian aircraft over foreign countries.

Q: How did you become a journalist? And what path did you take to get to where you are today?

A: I studied anthropology in college, and I had to write a thesis, and I went somewhere and had to conduct field work, which I really liked. And after college I thought that was probably pretty close to what journalism is, so I decided to become a journalist. And it took a long time, but it worked.

Q: How did you end up breaking into the industry in the first place?

A: It took a long time, and when I wrote “The Perfect Storm” I had been working for years a freelance journalist making very little money. And I really got lucky with that book, and I wrote a good book and it sold well. And then suddenly I had access.

Q: What advice would you give to aspiring journalists who are trying to create a career out of it?

A: You’ve gotta do things that interest you. I mean, you could go to Tripoli right now if you wanted to. Life is too short to waste your time writing about things you don’t care about. After years of being a freelance writer, I felt like I wanted to prove myself as a journalist to the world, so I decided to cover the war and genocide in Bosnia that occurred between 1992 and 1995. I literally hopped on a plane to Vienna with $500 in my pocket, and found a group of journalists who also wanted to cover the conflict. And contrary to to what you might think, there’s nobody stopping people from entering a war zone, it’s the opposite actually, most people are just trying to get out of there. So we jumped in a car and headed into Bosnia, and it all went from there.

Q: Is there something you look for in the topics you choose to cover? Or are there any overarching themesto what you’ve done?

A: I dunno…they have to fascinate me. And a lot of things fascinate me, so it’s hard to lump them together thematically. I mean, the stories that I cover overseas have important stories in one way or another that I think I can bring something to that maybe other journalists aren’t. And I think that with most of the domestic topics I’ve covered, like “The Perfect Storm,” I tend to write about sort of small, marginal groups of men, like people on fishing boats. There’s plenty of exceptions to that, but that does seem to be a little bit of a theme.

Q: How did you end up getting assigned to the story in the Korengal Valley in the first place?

A: I was already a correspondent for “Vanity Fair.” I convinced them that it would be a good idea to follow a platoon for their whole deployment, and they agreed. And then I got a video camera and started shooting video, they didn’t know about that, but I just decided to do it. They didn’t know I was gonna write a book either, but that didn’t matter, I was fulfilling my obligation to them as a journalist… Initially I got a camera from ABC news, I already had a relationship with ABC, I had a Sony D1. And then Tim and I bought a Sony Z1.

Q: Did you and Tim choose each other as a team to go to Afghanistan, or did your partnership there come about in a different way?

A: We were working as a pair, but we just weren’t always there together. We each went there for five months, sometimes together and sometimes not. I had already gotten the assignment, and I needed a photographer to work with. He already worked for “Vanity Fair.” And I talked to him to see if I thought he’d be a good match for me. And I made sure that he could shoot video, and he could, so that’s how we came together.

Q: What future projects do you have coming up?

A: Tim is going to Libya in a couple days and I’m joining him there in a couple weeks. Tim is working under a private contractor and producer, and I’ll be there for “Vanity Fair.”

Dragon Press entertainment reporter Ben Gill interviewed photographer Tim Hetherington in October. You can find the article and video here.

{jcomments on}