From 1989 to 1996, during the first of two bloody civil wars that ravaged the African nation of Liberia, warlord Joshua Milton Blayhi and his band of child soldiers known as the Butt Naked Battalion conducted a bloody campaign of terror, often while dressed in nothing more than an AK47 and a pair of leather shoes.

Blayhi, better known by his nom de guerre General Butt Naked, was born the high priest and spiritual leader of his native Krahn Tribe, a position which often required the ritual practice of child sacrifice and cannibalism. In 1996, Blayhi claims to have had a vision of Christ that told him to lay down his arms and spend the rest of life repenting for the countless sins he committed against the citizens of his country.

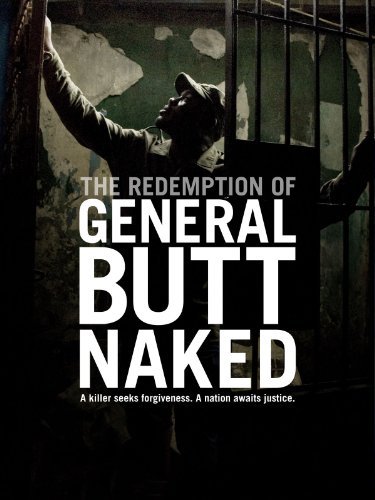

In a follow-up to the Dragon Press’s recent interview with the former general, Eric Strauss and Daniele Anastasion, directors of an award-winning documentary about his life, “The Redemption of General Butt Naked,” spoke with the Dragon Press about their film at the 2012 Independent Spirit Awards.

The pair spent five years investigating the complex life of the notorious Liberian warlord turned Evangelical preacher, attempting, in their words, to “explore the limits of human forgiveness” and the challenges of recovery for a nation scarred so deeply by death and destruction.

Dragon Press: What about Blayhi drew you guys to him most?

Strauss: Well, I think his story allowed Daniele and I to really tackle issues and themes that we found extremely compelling, such as issues of justice versus forgiveness in a postwar nation, issues of personal transformation. Could a figure like Blayhi really make that kind of a transformation after committing such horrific crimes? Could someone like that actually make that kind of a change? And those were themes that we were interested in before we even found out about Blayhi’s story…and once we heard about this man’s story it became…it was a deeply rich history to explore these issues. And that’s kind of what brought us to the story.

Anastasion: We had worked together at National Geographic, and we had done a bit of work filming in prison, and were already kind of keyed into…themes of justice and reconciliation and redemption for people who have committed atrocities. So, I think that these were questions that were already swirling in our minds. And Eric approached me with this story, and of course when we met Joshua we knew that there was the potential for an incredibly complex viewing experience there.

What are your own personal conclusions on who Blayhi is?

Strauss: That’s a tough question…As far as his genuineness in his transformation, or in his new beliefs, yeah I do think on some level Blayhi is very much sincere that he has left his past behind, he has left the killing behind, he has left the person of General Butt Naked behind him and is moving forward in his best attempts…to be a born-again Christian. Do I think he’s completely successful in that?…The answer would be no…For Joshua not only to balance the scales of his past, that would be somewhat insurmountable in a way given the crimes he’s perpetrated. So on the one level I don’t know that he’ll ever be successful in that sense…He’s still a deeply-flawed individual, but as far as genuinely trying…I would have to say that he is trying. {sidebar id=53}Anastasion: I think that there’s also the question of do you believe him, and then there’s the question of what about justice. Regardless of what you think about him, he still committed the crimes that he committed. And to some extent those are almost separate questions. I think that justice is always gonna be sort of looming for him. How is he going to pay for his crimes at some point like all of the perpetrators during the war?…The way I feel about him, whether or not he’s genuine, it’s constantly in flux based on the choices he makes. If I feel that he’s genuine right now, I kinda wanna know where he’s gonna be in ten years and what kinds of choices he’ll be making then. He’s a work-in-progress and there’s no way we can ever know.

How did you both decide to present Blayhi in the film?

Strauss: How to portray Blayhi’s character in the film was very much an evolving process because Daniele and I were very clear with Blayhi when we met him that were not Evangelical Christians, we were not necessarily coming from a position of faith the way he was approaching his life. We were coming at it as secular filmmakers. We covered and documented his story over the course of five years, and much of that was an emotional roller coaster. Trying to figure out where we stood…and did we believe him on this issue, did we believe him on that issue, how did we feel about this? There were times on that journey that I was extremely impressed by some of the actions that Blayhi took, such as coming forward to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). And then there were other moments where Blayhi would sort of grandstand in a church in Ghana towards the end of the film after he seemingly, genuinely approached a number of victims and sought their forgiveness, and hopefully gave them a sense of closure and healing…But then would the next day sort of grandstand about it to a church filled with parishioners. So it was a constant up and down with him and how to feel about him. And I still think a lot of that motivated how we presented him in the film.

Anastasion: I think that we tried to present him in all the complexity that we personally experienced. I think we felt almost an obligation to not present a very clear-cut, black and white story because the reality, the complexity of what we saw on the ground was so difficult to parse through, and so confusing. And we really wanted viewers to be able to wrestle with the fact that these concepts of forgiveness and redemption…it’s not easy. It’s sometimes questionable whether it can even happen, but it’s important to look at how difficult it is for this particular society.

Why was the Liberian Civil War so radical in its nature? Why were there child soldiers fighting in drag, why were there kids fighting naked? Why was the nature of the war so extreme?

Strauss: I wouldn’t claim to be an expert on the Liberian Civil War…I think in the case of Liberia…you’re dealing with a war where there were multiple factions. This was not a unified, government-trained army…You’re dealing with civilian factions, often based along ethnic lines bringing a certain cultural value system forward. And a lot of belief systems, however small they were, sort of came to the front during this conflict. A lot of children were recruited, as they often are in a lot of these unstructured wars across Africa sadly. And I think a lot of these belief systems got bastardized during the course of the war, you know all the things you hear about through journalism; you know dressing up in wigs and women’s outfits, the voodoo, the “African science” as some people call it, the cannibalism…these were cultural practices that were bastardized by these child armies, oftentimes drunk or high. I think a lot of that had to do with the spiral…I think in a lot of ways, it’s just a very poor country, not a lot of firm institutions there, legal or military institutions…And things really devolved quickly, and then over the course of, you know, basically 15 years, you have almost a generation being raised up in all of this chaos. And I’m not sure it would’ve looked all that different in many parts of the world if they went through 15 years of utter chaos and civil war the way that the Liberians did.

Can you describe some of the most visceral personal accounts you heard from people who were in Liberia during the war?

Anastasion: We interviewed for this film a number of former child soldiers who participated in the war. So I would have to say that their accounts of the crimes that they committed were probably some of the most difficult things that I’ve ever heard. There’s one young man who we interviewed who just matter-of-factly explained to us how he cut open the belly of a pregnant woman and took the baby out. I don’t know how you live with something like that, so these are the types of things that Liberians, not just this high-level general, but thousands of people are living with whether they perpetrated these crimes or whether they were victimized by people. And I think that there is a collective trauma in that society that will be very difficult to recover from.

Video by Ben Gill/The Foothill Dragon Press. An unedited version of the original video interview can be found here.