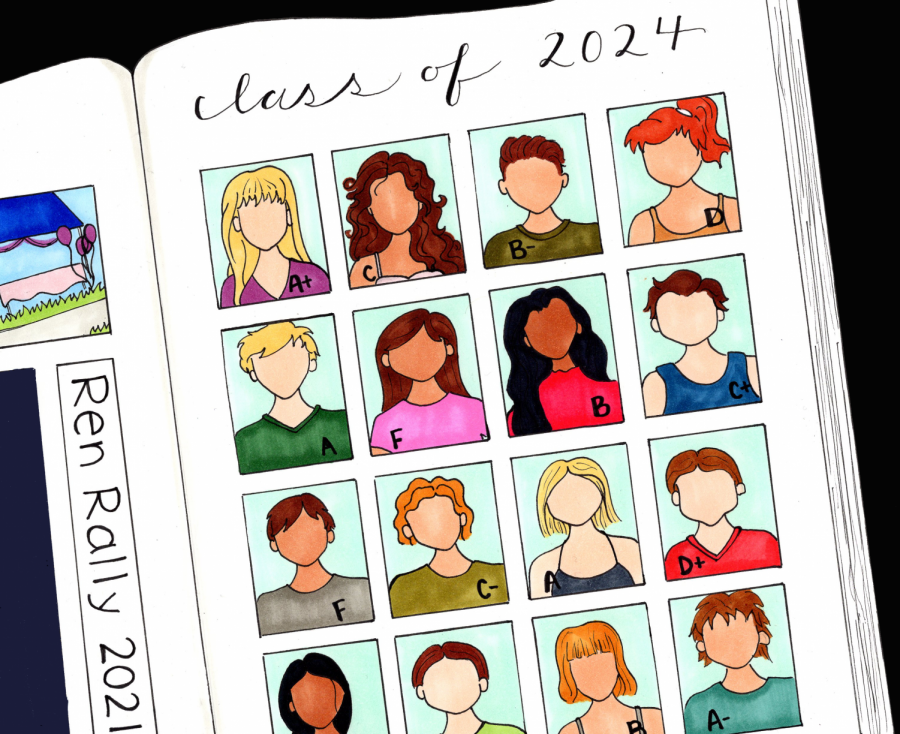

Opinion: Why Grades Deserve an F

The idea of grades serving as a way to communicate with a student has long since been lost

September 21, 2019

Grades are something that seem unavoidable. How else would teachers give feedback to students, parents, colleges, and future employers? In this short article, I will provide an evidence-based critique to try to prove that a seemingly essential aspect of the education system, letter grades, are deeply flawed.

I am not suggesting to completely abolish the grading system, rather, I will try to articulate how it can be amended, but first and more importantly, why it needs to be amended. The grading system is deficient for these three reasons: (1) grades reduce motivation to learn; (2) grades are intended to offer an objective measure of a students ability but instead are incredibly subjective; (3) grades do not give students descriptive enough feedback.

Grades decrease students’ inclination to want to learn something by replacing the intrinsic motivation that the student had with external motivation. An article written by Jeffery Shinske and Kimberly Tanner on the effects of grading, called “Teaching More by Grading Less (or Differently),”, found that “[g]rades can dampen existing intrinsic motivation, give rise to extrinsic motivation, enhance the fear of failure, reduce interest, decrease enjoyment in classwork, increase anxiety, hamper performance on follow-up tasks, stimulate avoidance of challenging tasks, and heighten competitiveness.”

Students who are interested in a subject, who want to learn for the sake of learning, can quickly lose that interest because the arbitrary standards to which they are held discourage inefficiency. So with any real desire to learn having been ripped away, a student is only left with the negative motivation, fear of failure. This fear is a good thing in that it prevents, at least somewhat, a student from not learning anything or not participating; but it cannot cause a student to desire to learn a subject. So students end up putting minimum effort into everything they do only because they’re afraid of what will happen if they don’t put in any effort.

The detriment to learning here is obvious: a student cannot learn something, at least not learn it properly if his only reason for learning is fear and his effort is minimal. And while students with higher scores “appear somewhat sheltered from some of the negative impacts of grades” this is the only silver lining to be found. Students with low scores, instead of seeing this as a chance to improve themselves, instead “generally withdraw from classwork.” So although grading can motivate higher-scoring students to continue to do better, it also strikes fear within lower-performing students by substituting the intrinsic motivation to learn with an external one and can cause less participation.

Grades are intended to give an objective measure of a student’s proficiency in a certain subject, yet a sizable amount of objectivity is lost due to the inherent subjectivity of material, teachers’ prejudices and grade curves. Is there a way to measure how well a student answers the prompt, how insightful his thesis is or how eloquent his style is? In short answer, no there isn’t. When answering this question, a scene from The Dead Poets Society is brought to mind where Robin Williams has all of his students rip out the introduction of their poetry books because the author of the introduction claims to have created a way of objectively measuring poetry.

That is the appropriate response to such hogwash. Suppose that a teacher was grading a student’s essay for English class: other than the obvious factors that influence the paper’s grade, like proper formatting, correct grammar and spelling, the grading of the paper is almost entirely subjective, and because points for grammar and formatting are usually a much smaller amount than those given to style or answering the prompt, the largest influence over the paper’s final grade now becomes the subjectivity and prejudices of the teacher’s grading. This dynamic is revealed in the aforementioned article, which “asked 142 teachers to grade the same English paper and found that grades on the paper varied from 50 to 98% between teachers.”

A counter to this is that the subjectivity of English itself is to blame for this disparity. I think this is a fair point, in that to blame teachers entirely would be unfair. Perhaps if we focus on a more objective subject, teacher objectivity will be clearer. How, for example, could the history of geometry possibly be subjective? According to Shinske and Tanner’s research, it is very possible. When 61 teachers graded the same geometry and history papers twice, the second time eleven weeks after the first, they concluded that the “variability of grading is about as great in the same individual as in groups of different individuals” and that the assignment of scores amounted to “little better than sheer guesses.” If that wasn’t convincing enough, prepare to hold back your gasps for this one: “penmanship of the author, sex of the author, ethnicity of the author, level of experience of the instructor, order in which the papers are reviewed and even the attractiveness of the author.”

Grade curves are equally problematic. A student who receives an ‘A’ in biology at one school could do just as well as another student who receives a ‘D’ in the same class at another school. All else being equal, the student who got a ‘D’ is unfairly judged to have been worse at the class. Curved grading carries the harmful possibility of portraying a person whose skills and abilities are wholly different than what they are in reality. Ultimately, grades cannot be classified as an objective measurement for two reasons: (1) certain subjects are subjective at their core, and one’s knowledge and or proficiency in that subject is impossible to objectively measure; (2) teachers have prejudices, and these biases are strong enough to make something that seems entirely objective, like math, subjective.

The final problem: Grading was created to increase the efficiency of feedback from the teacher to student, and while the grading process is very efficient, that efficiency comes at a cost of less informative feedback, and therefore less useful feedback. The letter ‘C’ simply cannot provide the same amount of information that a written response can. There are two types of feedback, descriptive, (feedback that indicates how a student can be more capable) and evaluative (feedback in the form of a letter grade, and judgment is given). The article found that “students receiving descriptive feedback (but not grades) on an initial assignment performed significantly better… than did students receiving grades or students receiving no feedback” Furthermore, the article finds that if both a letter grade and descriptive feedback are provided, the letter-grade is likely to cause students to ignore descriptive feedback. Assigning grades does not give descriptive enough feedback to improve students future work, and it can counter-intuitively reduce the likely-hood of students gaining anything from possibly-existing descriptive-feedback.

To fix the system, classes must lean toward grading for participation and effort instead of accuracy. Doing so will mitigate the harmful effects of grades. Also, “a grading system that rewards students for participation and effort has been shown to stimulate student interest in improvement.” Removing accuracy-based grading entirely wouldn’t be beneficial, but if accuracy-based grading and effort-based grading were able to be balanced, that new system would be more advantageous than a completely accuracy-based or a completely participation and effort-based grading system. Second, I suggest that teachers use rubrics as often as possible, especially for subjects like English. Doing this will reduce the amount of subjectivity in grading and allow students to see specifically where they did well and where they struggled. Next, I propose that teachers do not grade on a curve. Teachers could try to pinpoint what exactly on a test created the need for the curve, and remove that specific problem or set of problems from the students’ averages. Also, teachers can allow students to essentially re-do their work provided that the student did actually learn it the second time.

These ideas have the potential of creating a high enough class average to remove the necessity for a curve. My final and possibly most important suggestion is to become, as the article puts it, “skeptical of what grades mean.” While I have concluded that grading is not an effective means of evaluation, that is not likely to change anything, at least nothing in the near future. With this in mind, I earnestly encourage everyone who reads this, especially those with the power to make changes, to form their own evidence-based opinions on whether grading is beneficial to the education system.

Cherie Eulau • Sep 23, 2019 at 2:13 pm

This is an insightful piece . I’d give it an A (that’s irony). We also need to evaluate kids on how much they improve. If a student walks into Spanish I and already knows 50 words and the goal is to know 50 words by quarter one should that student get an A if they still only n the 50 they walked in with? If your writing show a lot of improvement, shouldn’t you get an A?I wish we could get rid of grades complexity. It is by far the least enjoyable part of my job.