This article will mostly be read by American eyes, and because American culture is extremely pragmatic and primarily interested in “what will put a dollar in my pocket,” the topic of it, Eastern philosophy, may be perceived as “lacking value” to some readers. Americans often joke, even, about philosophy majors, saying things like “Lotta lucrative career prospects there, eh?” They don’t see the value in examining questions like “Why is there something instead of nothing?” and “What is beauty?” and “What is justice?” That which has the most monetary value has the most value in America. That which earns the most money earns the most dignity in American culture. It’s a crime in America to be poor.

Eastern Asia, on the other hand, has men who were poor but also wise and virtuous, and therefore they were more highly respected than men of great wealth. America is a nation of poverty, yet those in poverty blame themselves for their inability to garner wealth. They lack a sense of dignity and purpose. Inversely, the culture and philosophy of Eastern Asia dignifies their poor and finds value in asking the deeper questions of life, even if it doesn’t fill up their wallets.

In order to examine how philosophy has shaped individual societies throughout Asia, we have to investigate the differences in the thought systems which have encompassed each society, as well as take a look at what these differences have meant to the society’s culture as a whole.

You may remember that the 2008 Olympics, hosted in Bejing, China, kicked off with a quote from a philosopher named Confucius: “To have friends coming in from afar, how delightful!” Later, thousands of performers dressed as Confucius’ disciples and paraded through the stadium. Clearly, the Chinese like this guy.

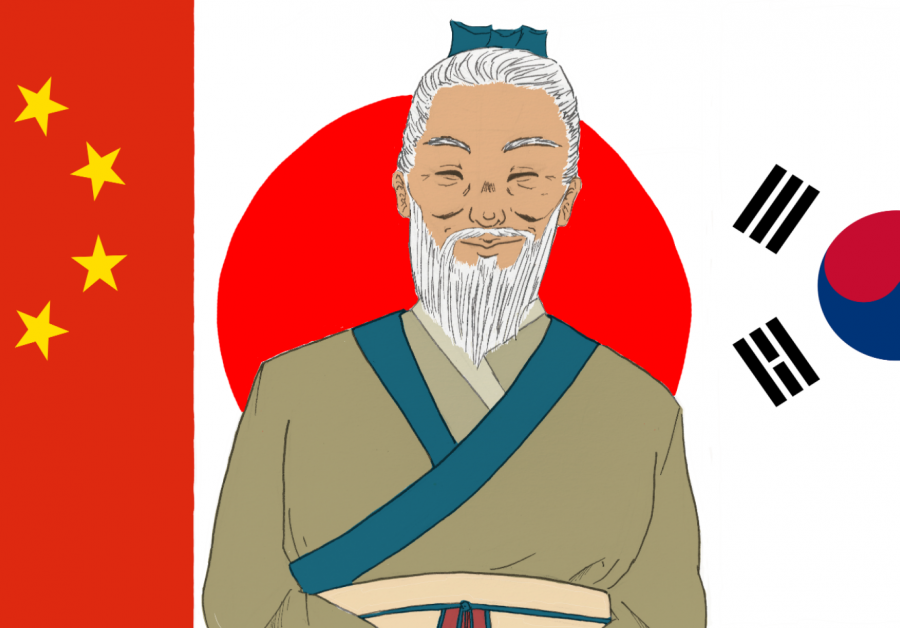

Confucianism, the primary school of thought in Eastern Asia, originated in China and later branched off into Korea and Japan. The most esteemed philosophers in Korean and Japanese history are, in fact, Confucianists.

There is huge diversity in human culture, ranging from what we eat, to where we live, to disparate moral and political systems, to wholly different worlds of thought. The world we live in isn’t host to just one model of reality. It’s full of unique manifestations of the human spirit. Within Eastern Asia alone, the philosophical outlooks of China, Japan and Korea vary greatly.

Philosophy itself is embedded in the very world it aims to understand, and thus it is distinctive to the separate experiences and histories of the individual communities it aims to inform. Because the expanse of Eastern philosophy is so wide and its ideas so broad, this article will focus on the three strands of Confucianism which branch off into China, Japan and Korea. Confucianism is a cultural commonality that all three countries share.

There are Confucian reflections on the moral heart and mind in each of their similar, yet distinctive, modes of thought. But there are many different branches of Confucianism, and each country is its own brainchild of these teachings. They’ve each internalized Confucianism, among other thought systems, to develop their own unique philosophy, culture and focus. This localization of Confucianism is a natural part of the international cultural exchange, and we need to respect the distinctive traditions developed in each country.

Confucius became a renowned Chinese thinker in a period of political decadence and spiritual questioning. He sought to bring peace and order to a society of people suffering from hunger, displacement and death. Political turmoil, marked by a fight for dominance between several independent kingdoms in ancient China, was a hallmark of the time period. Confucius strived to teach others how to live together in harmony as well as principles of good governance. He also taught that the safety of a society depended on the people maintaining and strengthening five key relationships: ruler to subject, father to son, husband to wife, elder to younger and friend to friend.

For China distinctively, Confucianism was needed to escape political upheaval. The teachings of Confucius fell right along the lines of what the society needed at the time. The philosophy is adaptable and accommodating to the needs of an individual system at a given time. It isn’t any one thing. It’s about how people relate within a society, how they interact and how they support one another. And it all branches from the very humanistic idea that each individual is inherently good, unique and powerful.

The influence of Confucianism on Chinese government is in stark contrast to a government that invites its citizens to wring out whatever unlikely chance and opportunity for exceptional wealth that they can get. Confucianism teaches how a society can be virtuous, harmonious and responsible for the well-being of all its people. It puts livelihood and prosperity over riches and glamour.

Interest in Chinese literature during the Goryeo dynasty (918-1392) molded Korean philosophy into a form of Confucianism which had been melded to Taoism and Buddhism, called Neo-Confucianism. Neo-Confucian thought emphasizes ethics and the government’s moral authority. It demands for character to increase as power increases. Rather than focusing on the morals of an individual, it focuses on the morals of the entire country.

In contemporary Korea, the prominence of Confucian thought as the dominant ideology has faded. This is because Confucianism was considered as something that hindered voluntary modernization of the Korean nation. Liberalism, democracy and the parliamentary system were introduced in Korea, rendering Confucianism insignificant in the eye of its political system.

What remains of Confucianism is its influence. In statistical studies, it would appear that Confucianism as a religion had nearly died out in Korea but these statistics can be misleading, as a lot of Confucian ideas and practices still saturate Korean, and particularly South Korean, life. Confucianism focuses heavily on education, and this remains vital to South Korean culture. Confucianism’s emphasis on family and group-oriented ways of living is also cemented in South Korean daily life.

Japanese Confucianism focuses on the relationship between humans and their natural environment. It dissuades citizens from acting on the impulse to breach the planetary boundaries within which humanity operates in order to find refuge in an over-embellished monetary status. It discourages the dream of material things and esteems self-reliance and spirituality.

Confucianism is the intellectual force defining much of the East Asian identity of Japan. The Tokugawa period in Japan was dominated politically by a samurai regime led by a hereditary commander-in-chief. Because Confucianism has the tendency to look to the past, the Japanese sought to return to a supposed “golden age” with the teachings of Confucius as the catalyst for political transformation from the Tokugawa rule to the Meiji imperial regime.

However, as the Meiji period went on, Japanese philosophy took a turn from traditional Confucian ideals and more towards Western philosophical ideals. Thus, Confucianism slowly began to wither away in Japan. But Confucian discourse did not entirely escape them. Many of the Meiji leaders of the time period had backgrounds in Confucian studies, and so their understandings of liberty, equality and natural rights stemmed from Confucian teachings.