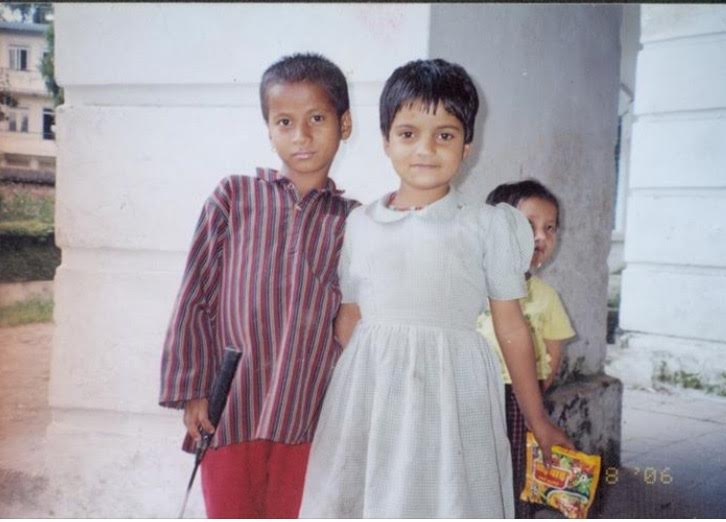

Two Nepali-American Foothillians, unrelated by blood, religion or gender. Two white, Venturan mothers. What binds the four together? To start, the last name McCullum.

Kahar McCullum ‘17, the eldest sibling of the family, believes he definitely has an interesting story, one that can’t begin to be captured by those mere 31 words. The life he knows today began at age six and a half, when he was adopted from an orphanage in Nepal. He had spent about a year and a half there, and had watched his younger brother get adopted by an Italian family before him. In Nepal, there are rules against adopting siblings together, because of some “emotional consequences that could happen,” said Kahar with a slight tone of frustration “It’s BS.”

After he got adopted, he remembers going to the Yak and Yeti hotel in Nepal, where he was overwhelmed by the “the availability of everything so quickly and the food” in a buffet line there. Something as simple as a buffet line proved very difficult for Kahar, who lacked the height to see the foods and the experience with English to understand his mother’s descriptions of them. He remembers that his mother would show him the food and he would either nod, shake his head, or point to something else.

At first, he didn’t like American foods, but, like many other cultural differences, he grew accustomed to it with time. He still especially enjoys spicy foods, which he thinks “definitely comes from my heritage and from my background.”

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/327930509″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Upon arriving in America, he was thrust into an unknown world and forced to adapt quickly. He says he didn’t really experience culture shock, but felt confused by many simple differences in culture. For example, he had grown accustomed to using his middle finger as a pointer or to trace where he was reading because, in Nepal, it has no negative connotation.

It was a bit frustrating that “I was constantly told not to do that and I was never told why not to,” he said.

This is just one example of the “cultural differences” he noticed. “There’s just tiny stuff, just cultural differences, that sometimes I even to this day will think ‘oh that’s weird,’” he said.

For the most part, these differences didn’t bother him, and he was able to find a balance between the parts of himself formed by Nepalese culture and the parts of himself he was finding in America. However, finding that balance included sacrifice on both ends, and there is one thing that, above all others, he wishes he could’ve kept from Nepal: language.

“Because I was forced to assimilate so quickly I had to leave a lot of my language behind. Not that I left my beliefs or my culture because that’s something that I think you can’t really take away from someone, but language I think you can definitely take away from people,” he said.

Because of this, “I don’t really know my native language. I wish I did,” he said. Instead of dwelling on it, he chooses a more positive outlook, believing “that’s just the way of things and I’ve just got to appreciate that I still have my culture.”

In addition, it’s a comfort to know that he can still learn to understand people in Nepal or the surrounding region with practice. In particular, he’d like to learn to write in Sanskrit, because it’s “one of the most beautiful languages that I can think of.”

As he adjusted to American culture, he found a dislike for being an only child.

“I decided being a single child was alright but there was too much attention on me and I couldn’t get away with stuff,” he said. “So, I told my parents that I wanted a sister and they went through the process and they got my sister.”

The other half of the McCullum siblings is made up of Kahar’s younger sister, Aasha, who was adopted a few years after her brother.

Aasha recalls the day of her adoption very vividly. One day after school, Aasha was told to dress in her nicest clothes and report to the main office. As a known troublemaker, Aasha assumed she was in some sort of trouble.

“I got overwhelmed; every step I took was heavier and heavier. I felt like I was actually in trouble or I was getting sent away because I did something bad, I always did something bad,” she said.

Aasha soon realized that she wasn’t in any type of trouble when she saw the woman who would soon become her mom. With a smile, Aasha shared that as soon as she saw her soon-to-be mom that “everything just fell into place.”

“Previously, people had explained to me what adoption was. Their version was that you get to go to this different world where people can fly and everything just appears and there are no struggles at all. It was like a formation of Heaven,” she explained. “I mean I didn’t believe them, but I did [believe them] enough because I wanted to be outside of the walls that caged me in.”

During Aasha’s first plane ride to the United States, she got sick so it wasn’t as enjoyable as she had expected. But, when Aasha and her mom landed at Burbank Airport, her other mom and brother were waiting for her.

“I didn’t expect this but I had another mom and a brother, Kahar. So I ended up having a bigger family than I expect and that was so awesome,” she said.

As siblings, Kahar and Aasha share many similar experiences going through high school and transitioning to a new culture, but they differ in memories of their life in Nepal. Where Kahar remembers little of his life before being taken to the orphanage, Aasha can recall quite a bit.

“My life in Nepal[…]wasn’t bad. It was just something that I was used to,” Aasha said. “I had plenty of friends I used to run around free outside, going in the jungle. I never knew about technology or cars.”

After her family moved to the city of Nepalgunj, Aasha’s sister was taken to the orphanage. Just a few days later, when she was around six years old, she was removed from her life and family in Nepalgunj and taken to live in an orphanage.

“People will ask me what happened to my parents, but I couldn’t say,” Aasha explained. She doesn’t know why she was taken from her parents. “And basically, I was left [at the orphanage] and I was so scared. I had never been to this place before and I didn’t know where my family was.”

Aasha told the story of her second day at the orphanage when she decided to run away. She gathered her few belongs and began to run from the building, but little did she know there was a gate.

“The guard caught me, and I got my first spanking there,” she said. Since then, Aasha was known as a rebellious kid.

For Aasha, life at the orphanage wasn’t too bad; it became her life in Nepal. She would wake up early in the cold morning to do chores such as laundry or weeding. At the orphanage, Aasha had schooling where she began to learn English for the first time. She explained that occasionally, the orphanage would dress some of the girls in saris and take them into the city to eat food or go shopping as a spiritual activity. Aasha particularly liked to escape her school for the day.

At home, the McCullums, as you might imagine, live a normal family life. However, some of their disagreements are made more complex by the great mix of cultures in coming into the household. Kahar never really thought about these things much, but does recognize religion as one of their more “interesting” differences.

Kahar now classifies as a Deist, but comes from a background of Buddhism, as many Nepalese do. Aasha comes from a background of Hinduism and is considered a Brahmin within that religion. His mother comes from a background of Mormonism, and her entire family is Mormon, but she now considers herself apart from Mormonism as a Christian.

This makes for some interesting discussions in the home.

“There’s all these different religions coming into contact and I think that’s really interesting because we have so many huge discussions about religion,” he said.

“I think that is mostly due to our background because I don’t think we’d ever be subjected to that kind of conversation if we didn’t have that kind of background, if I didn’t come from a background of Buddhism or that my sister didn’t come from a background of Hinduism,” he continued, and “it definitely makes some dinner table conversation interesting and I think it also shows the light on to other people’s beliefs.”

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/327939933″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Luckily, the family is very open to experiencing new cultures. As a family, they’ve traveled to six of the seven continents, all but Africa (and yes, that includes Antarctica) but haven’t yet gone back to Nepal. Kahar does wish to travel back there someday, but his sister is more cautious. She’s never been back to Nepal either, though not for her mother’s lack of trying.

“My mom keeps nagging me ‘When do you want to go back to Nepal?’” Aasha said. “I’m just afraid to go back because it will bring back the memories that I had. I don’t know what it is going to be like, and there are so many memories that I have shut out that were painful for me. If I were to go back, they would come back to me.”

“I want to go back eventually but I think that if put it back farther and farther every time, I will never end up getting there,” Aasha concluded.

The closest she’s come was a few years ago when she reconnected with her biological brother in Nepal through her mom’s Facebook profile. She learned her exact age, which is currently 16, and that she has many more siblings; some of which were adopted and others still live in Nepal.

For Kahar, the family’s emphasis on traveling has helped him to further develop an open mindedness he finds in many people with diverse backgrounds.

He thinks people in America tend to think that America is influencing the rest of the world, which he thinks is true to an extent, but on the other hand “if you look at the Constitution, if you look at the government, if you look at politics, it’s all originating from Europeans and how they have, throughout history, run their government,” he said.

Kahar finds it interesting that, despite this, “so many people are almost against diversity and against other nations and yet their very roots are from that and they just don’t know it.”

That’s why he finds traveling so important, because, often times, people who find faults in other cultures haven’t had the opportunity to travel and experience them first hand.

“I think that’s what’s great about people who have come from another nation or have a different background is their openness, their open mindedness, their ability to see something and just be like ‘that’s alright,’” he said. “I think it’s important for that to happen.”

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/327930738″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Similarly, Aasha is thankful to have the knowledge of cultures that she does.

“I like to know about the world. When I was in Kathmandu, I never knew that a bigger world existed outside of the small town I lived in. I knew everybody in that town, […] but I am grateful that I did get adopted because I was able to experience what I have,” Aasha shared.

With his background, Kahar had a firsthand experience with poor education in third world countries. He remembers waking up at six o’clock in the morning to walk to school.

At school, “we learned absolutely nothing,” he said. Having this experience with school in Nepal, where there is a “very poor education,” he knows he “wants to change that.”

After graduation, he plans to pursue a career as a teacher for kids who, like him, struggled to find quality education in third world countries.

“I know I can’t do it by myself,” he said “but I think that people who come into contact with me, if I can’t change the whole academic system or the school system itself, I can at least reach a couple people’s hearts and a couple people’s minds. So that’s my goal.”

Due to the fact that Aasha received poor education in Nepal and only learned a small bit of English at the orphanage, her first two years of her new life in Ventura were rocky. She didn’t have many friends and school was difficult. It was hard for her, because she was used to playing outside often with lots of friends but her new life was a stark difference.

Having such a unique blend of cultures in one household has taught Kahar that “the power of diversity is important, [but] to accept diversity is even more.”

In fact, if he had a list of things he would change about the world, the non acceptance of diversity would be at the top because “if we accept diversity, I think it broadens our mind to the possibilities,” he said.

Matt Demaria • Jul 10, 2017 at 10:28 am

Fascinating story about these two Nepalese students. I had a Nepalese student in my 5th grade class this year, though she lives here with her birth parents. Nice job, Abby and Chloe!

Anonymous • Jun 15, 2017 at 7:39 am

This is a well written article and a beautiful story about a brother and sister. However, my personal perspective is that these two siblings are very much “related”. I come from an adoptive family and find some of the language in this article offensive. Just because two people are not genetically linked does not mean that they are unrelated, and they are bound by so much more than just a common last name.