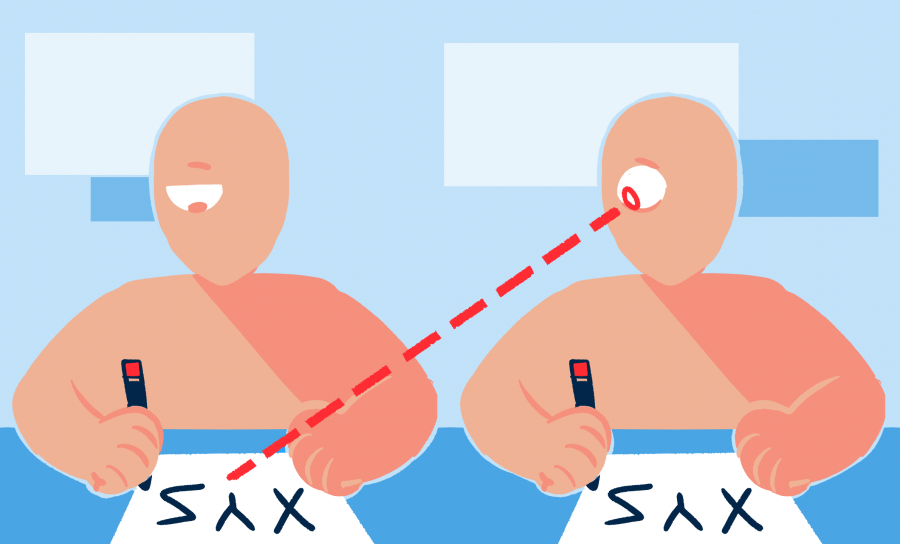

It’s a problem every teacher has to face, regardless of grade, school or subject; it implies self-degradation, loss of trust and a ruined transcript. It brings to mind math formulas written on the back of an eraser, answers scribbled on the wrapper of a plastic water bottle, questions hurriedly entered in an iPhone hidden under the desk by a student with a pounding heart and bated breath.

Cheating.

In a survey of 24,000 students in 70 different high schools, 64 percent of students admitted to cheating on a test. Even more shockingly, 95 percent said they had participated in some form of cheating whether it was on homework, tests or assignments. With such overwhelming statistics, it seems obvious that cheating has become the norm.

Cheating has always existed since time immemorial. There will always be someone out there who feels the need to take a shortcut without setting aside time and effort to achieve things through solid work. The bigger question is why are there so many people who cheat?

Cheating must, in some ways, be attributed to success. Success has always been ingrained in the American psyche. To high school students, success usually comes in the form of good grades. Our heavy reliance on education and values of academic achievement create a crushing burden on students to perform brilliantly in the academic arena. The value system results in a cutthroat competition to be number one, or at least to be able to hold your own against a tidal wave of intelligent peers.

The overemphasis on an “A” is enough that the consequences of cheating pale in comparison to one’s own moral code. Students are pressured by expectations from teachers, school administrators, peers and especially, parents. They feel desperate. The academic environment in which students live today bears startlingly similarity to French society in “Les Misérables” where an unjust system forces good people into beggars and criminals.

Although cheating contains an element of choice, for some people the “choice” is no choice at all. The so-called “alternative” is a “D” on a high school transcript or a rejection from a desired college. So what do students do? They cheat.

In a similar vein, teachers and parents also have to stop calling students “smart” as encouragement. The word “smart” implies a naturally occurring source of intelligence, unachievable by hard work. However, commending students for working hard shows that attaining their goal doesn’t necessitate natural brilliance. It also motivates students to work harder, rather than fixating on maintaining the appearance of being intelligent. Being raised that one has to be “smart” in order to succeed is dangerous because students will most likely see no other alternative than either cheating or failing.

Despite teacher protestations that they wish to emanate the belief that they trust students and taking steps such as confiscating phones and walking around tables would be a betrayal of that trust, teachers should view preventive measures more as removing “temptation.” By choosing not to, they also share the blame in knowingly creating a circumstance that encourages cheating.

Although harsh punishment may deter cheating, it can produce mixed results. Often cheating means failing a course or turning into a class pariah. Obviously punishment should be mete out when punishment is deserved but very harsh treatment shows a society unwilling to believe in second chances. Teachers should deal sternly with the offender, but instead of turning their backs on those cheaters for the rest of the year they should help students by getting to the root of the problem. Instead of treating the moment as a dead end, a moment that irrevocably ruins the future, it should be a chance for students to learn from a mistake and atone. After all, students are in school to learn, right? We are here because we are in need of guidance.

At the end of the day, we need to be reminded that all human beings are fallible and one mistake should not define someone for the rest of their life. In some cases, severe punishments could tarnish a student’s reputation for life. Whatever system judges students thus administers clumsy justice at best. Such actions would not only haunt their academic career, but result in review by future employers.

Cheating does not deserve a zero-tolerance approach but it doesn’t merit a completely tolerant one kids can take advantage of either. Instead of simply condemning cheaters, the school system needs intense focus on the task at hand and battle cheating as one would a disease. To teachers: provide a punishment that, while fair, is also rehabilitative in nature.