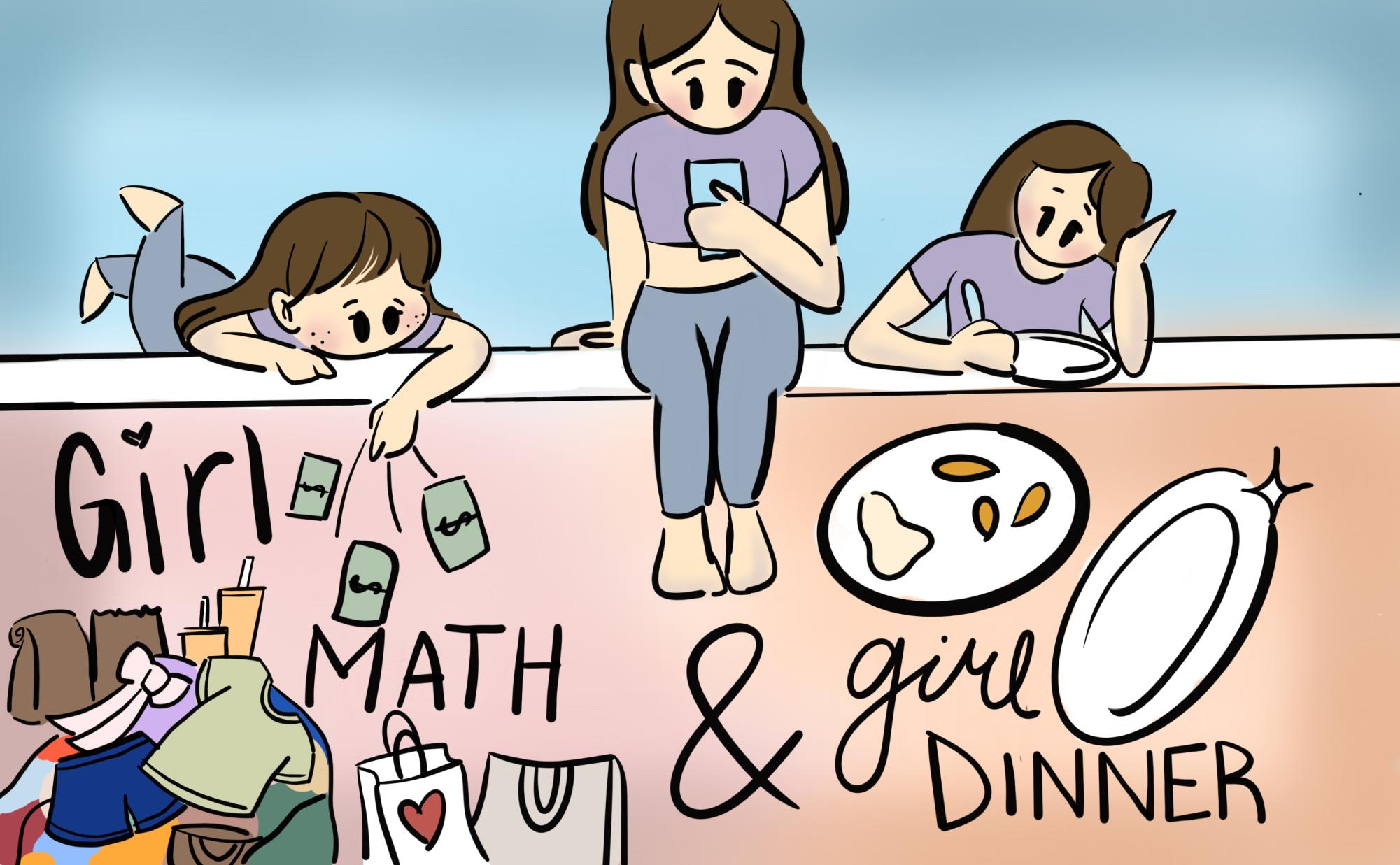

“Have your cake and eat it too”: Is TikTok right about healthy eating and spending?

The saying, “birds of a feather flock together,” couldn’t be truer than on the internet, where TikTok’s algorithm can categorize you as a gamer, fashion enthusiast, literary intellectual or Starbucks dependent within five minutes of scrolling. The fine line between being just a person or an internet user is getting ever thinner and every five minutes there seems to be an alarmingly empathizing TikTok made about your admittedly bad habits. Online trends have not only become girls’ best friends, but turned the ever-relatable social media platform into a sort of game—your style, your interests and your personality place you and others in this world of unsaid rules and rationalities defined by your real-life experiences, and you can play up your part by spending as encouraged. In other words, there’s no better way to intentionally or accidentally tempt people’s urges to spend to their hearts’ (or their Instagram feeds’) desires than on social media.

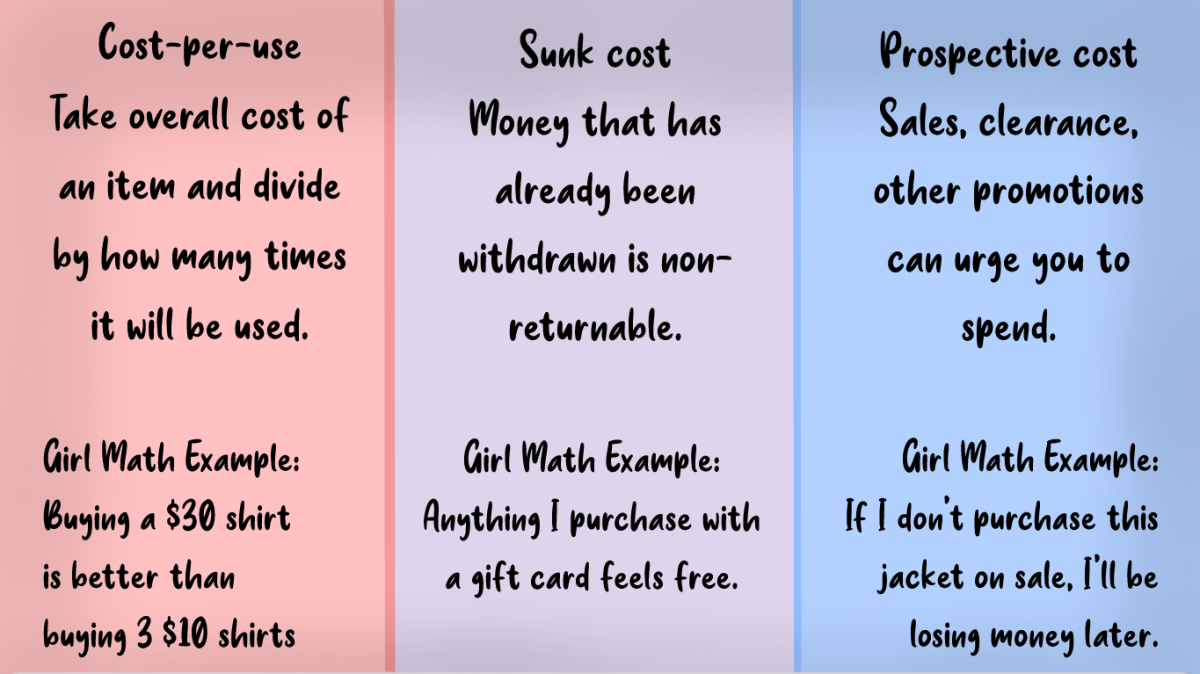

The newest in-group are the proponents of so-called “Girl Math,” which is a collective rationale helping girls justify everything from daily coffee runs to $4,600 tickets for Taylor Swift. Coined by New Zealand podcasters Carl Fletcher, Vaughan Smith and Hayley Sproull, the “Girl Math” segment helped listeners (usually adult women) think through their purchases, known as mental accounting, using a few key economic principles for support. These include cost-per-use, sunk cost and prospective cost.

Food to-go and clothes are the two largest spending categories for teens, with sunk and prospective costs being the two main principles that drive so many purchases in spite of “Girl Math.” “Girl Math” users agree that $5 or cheaper purchases and cash purchases “feel” free, and considering that paychecks come as lump sums, not small bills, spending in $5 increments certainly seems inconsequential. A large part of Girl Math is constituted by the idea of sunk cost, in which money that has been long since accounted for in a bank account, such as that loaded onto a Starbucks card, gift card or a $20 bill found in a jacket pocket, is “free” money. Additionally, direct depositing, Apple Pay/Apple Wallet, as well as the plethora of peer-to-peer payment apps like Venmo and Zelle, have eliminated the sense of urgency when paying with cash, making everyday spending seem like a no-brainer, even when it isn’t.

Of course, not everyone has had a rosy reaction to “Girl Math.” Some women are quick to distinguish how the trend can highlight misogynistic stereotypes of women’s spending, however it is important to not dismiss the trend as a one-way street. Video game companies have found various ways to market themselves and their in-game perks—besides food and clothing, Business Insider lists video games as one of the top spending categories among teenage boys, with games like “Valorant” reporting revenue of up to $20 million for a single set of weapon skins. Just as it’s unwise and unhealthy to spend money on daily Starbucks runs, impulsive video game purchases can be just as detrimental to personal spending habits. While “Girl Math” doesn’t just apply to how girls spend their money, it’s not always about how far a dollar can stretch, but whether what you want is worth spending on at all times.

It’s no secret that TikTok is a social media platform teeming with misinformation. On this highly addictive app, anyone can say anything, making it difficult to differentiate between fact and falsehood. Algorithms can push this potentially inaccurate information to the masses and all of the sudden, one video may have an audience larger than ever intended by the creator.

Although TikTok trends circulate quickly, they can have a lasting and potentially harmful effect on many individuals. With an astounding 1.3 billion views on TikTok, “Girl Dinner” is a recent trend that evolved from a seemingly innocuous cheese plate video to a viral concept that, in some instances, normalizes and promotes disordered eating behaviors.

In May of 2023, the mere concept of “Girl Dinner” came to the forefront when content creator Olivia Maher uttered the fateful words, “This is my dinner … I call this girl dinner,” before panning to a “charcuterie” style plate, complete with an assortment of cheese, grapes and pickles. Seems harmless, right?

Not exactly. In an ode to TikTok’s unpredictable nature, this phenomenon went viral. Soon, a theme song had been created and millions of videos and parodies of people sharing their own “irl dinners” were taking the app by storm.

TikToker’s came to the consensus that “Girl Dinner” can be anything you want, from a bowl of pasta to a single cracker. Not in the mood to cook dinner? No problem, a bag of chips and a diet soda will do the trick. While there’s nothing inherently wrong with swapping a proper meal for some snacks on occasion, “Girl Dinner” reached a point where “for you” pages were being bombarded with concerningly small portions of food labelled as “meals.” As the trend evolved, it began to reinforce the idea that women don’t need to properly fuel their bodies and this message has many negative consequences.

According to the National Organization for Women, 53 percent of American girls are unhappy with their bodies and this number jumps to a staggering 78 percent when girls reach the age of 17. Dieting is a very prominent aspect of American culture and women are exposed to myths of “Diet Culture” from a very young age. Largely due to unrealistic societal beauty standards, many women are convinced that they must change their bodies to meet external expectations. Food and body image is already a sensitive topic that is exacerbated by social media and the “Girl Dinner” trend specifically feeds into the stereotype that women should eat less than men.

When TikTok feeds are taken over by videos of strangers calling sparkling water and carrot slices “dinner,” it can trigger a downward spiral of comparison and self criticism. Thoughts like, “Is it wrong for me to eat a large meal at dinner time?” or “Why am I still hungry when so many people are satisfied by a bowl of popcorn?” are likely to cross the minds of viewers.

The “Girl Dinner” trend makes it seem common, acceptable and even preferable for women to inadequately fuel their bodies. Some will make the argument that “Girl Dinner” is in fact empowering to women, by relieving them of the pressure to spend ample time in the kitchen preparing elaborate meals. But it is necessary to consider the fact that this trend is reaching highly vulnerable audiences, such as young women and girls. Psychology professor Dr. Jessica Saunders, told Women’s Health, “The target audience for much of TikTok are adolescent girls who might not understand what normal intuitive eating is and might think, ‘This is what I’m supposed to eat for dinner.’”

Even if many of the videos are intended to be comedic, glorification of under-eating is harmful to everyone. “Girl Dinner” is just one example of how trends can unintentionally promote detrimental behaviors and serve as a reminder to always stay cognizant of the content we are consuming on social media.