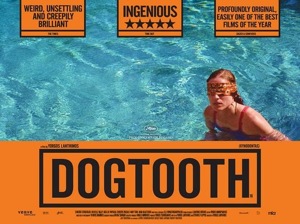

The Greek film “Dogtooth” (“Kynodontas” in Greek), directed by filmmaker Yorgos Lanthimos, retains many of these qualities common to indie films, and while it certainly incorporates them well, it’s the extent and overkill to which the director goes to convey his intended themes that makes this film a giant thumbs-down for me.

Is it weird? Yes. Is it controversial? Without a doubt. But just because it contains some of these elements doesn’t necessarily make it worth watching.

“Dogtooth” sets out to explore a single question: what happens to the human condition when one is cut-off completely from the outside world, along with all of its influences? In the case of “Dogtooth,” the disturbing interactions of three siblings, two sisters and one brother, are explored as they are forced to live out a truly bizarre existence at the country estate where they were born and have never left.

The parents of the three children offer little to no explanation as to why they have chosen to go to such lengths to not only shield but to also imprison their children. Other than a bizarre desire to completely control the mental and social development of their offspring, one can only guess at the sinister motives that are at play within this family.

In their never-ending quest for domination over their children, the parents even go to such extremes as to teach their children the wrong meaning for any word that comes from outside their home. For example, they are taught that the word “telephone” means “salt shaker”, and that a zombie is a small yellow flower. The children are also, rather unsurprisingly, told that the outside world is a place of death and despair, and that they may only leave the confines of their estate when they have lost their “dogtooth.”

It doesn’t take a lot of effort for one to identify the strange effects that this ironfisted isolation has on these three children in the film. The three kids seem to constantly be on the verge of either murder or incest with one another. And, eventually, this isolation does manifest itself in the form of extreme acts of violence among these next of kin, and even in sexual relations between brother and sister, and sister and sister.

It’s this extreme violence that finally pushed me to the point of pure disgust with this film. The basic subject matter is not what causes its downfall in my mind; it’s the utter excess to which the film goes to display its intended themes that makes me dislike it so much. Rather than subtly implying any of the disturbing themes of this film, Lanthimos instead decides upon showing the viewer various scenarios so unnerving and so graphically real that one can’t help but be disturbed.

While some may view this as an artistic choice on the part of the of the director, I don’t see the point in adding things like extremely graphic scenes of sexuality if they don’t in some way add to the plot, theme, or meaning of the film. Thus, when this film is closely examined, a cinephile would be hard-pressed to find any real purpose behind these specific plot elements. They may help deepen one’s understanding of the emotional state of the characters, but this could have easily been accomplished far better by other, less lurid means.

To the credit of Lanthimos, the cinematography in the film is simple yet oddly beautiful, the in-depth study of the human psyche is undoubtedly fascinating, and the themes it explores are also intriguing. But despite these positive points, the negative aspects of the film caused by the sheer gratuity with which it is told make it something I wouldn’t touch with a twenty foot pole. In the end, what this film amounts to is nothing more than an exercise in the depraved and perverted.

Not For Most

Rating: 4.7 out of 10