Cars have always been an integral part of American culture. Or have they?

Although it’s hard to imagine the United States (U.S.) without the prevalence of the automobile industry, there was a time when the streets of New York City, Chicago and Los Angeles weren’t eternally congested by cars, cars and more cars. The push for car-central urban planning was automotive corporations’ deliberate, private agenda, resulting in the car-biased society most recognize today.

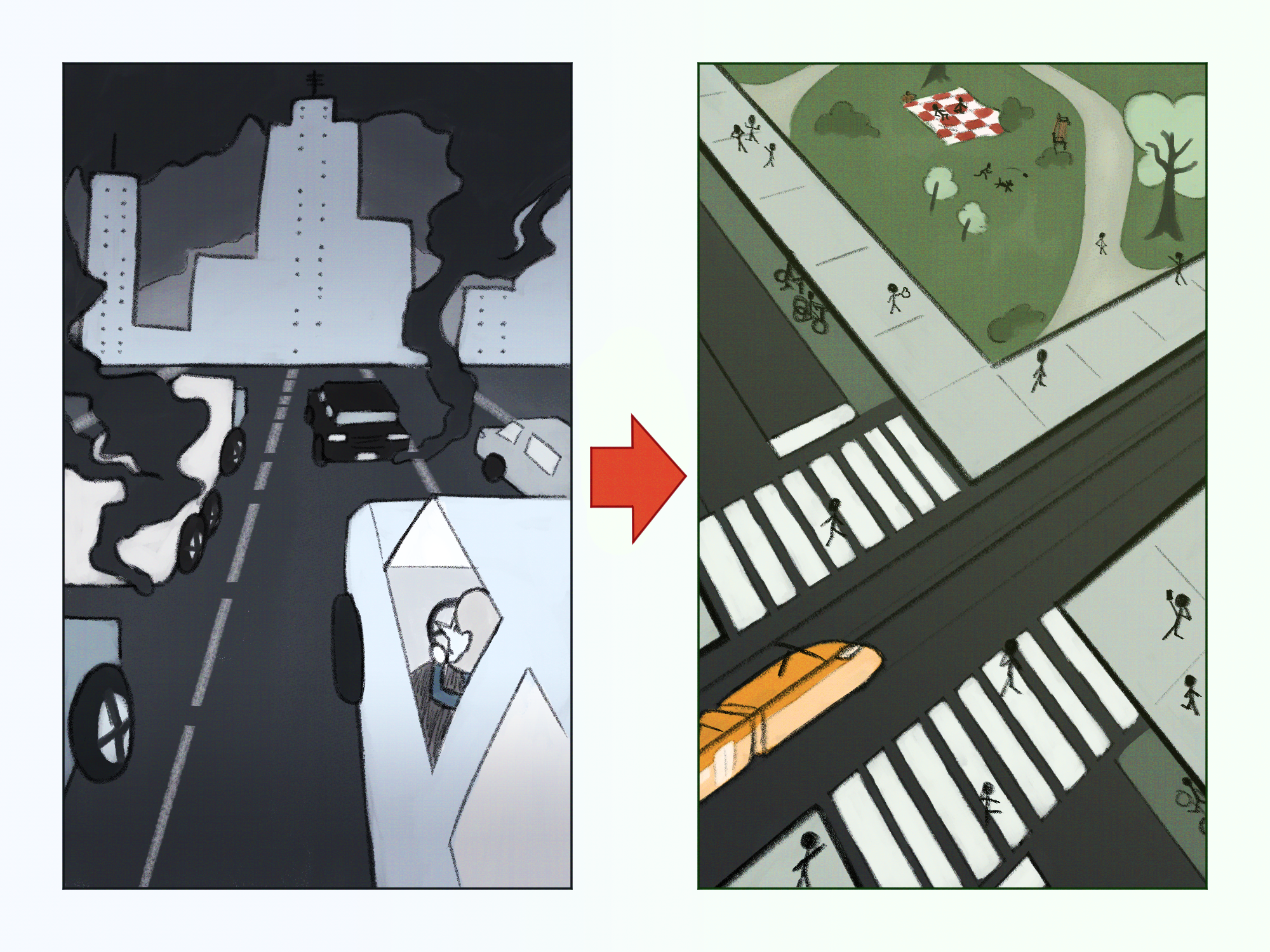

But what if that can change? Statistics have repeatedly shown driving’s many potential dangers, high contributions to greenhouse gases and correlation to decreased physical activity. It’s time to start thinking of urban planning that prioritizes its inhabitants before cars.

Dissecting America’s obsession with cars

Even so, a professor from the MIT Press Reader explained, “Motordom, however, had effective rhetorical weapons, growing national organization, a favorable political climate, substantial wealth, and the sympathy of a growing minority of city motorists. By 1930, with these assets, motordom had redefined the city street.”

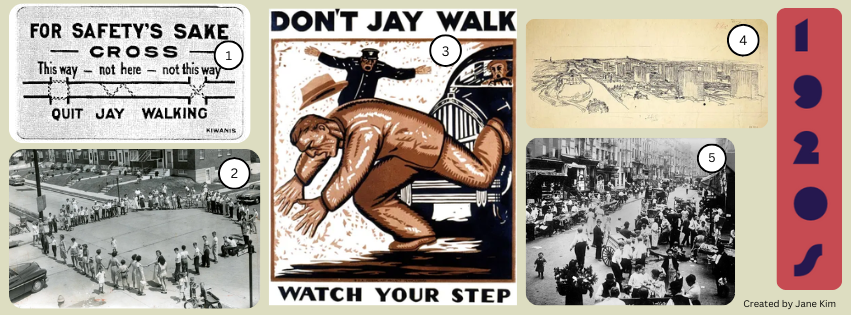

Once upon a time, pedestrians, not cars, ruled the roads. Each pedestrian death by automobile accident was an unacceptable tragedy, illustrated by the parades and dedication ceremonies of cities in the 1920’s for the hundreds of children killed every year in traffic accidents. Americans went to court over pedestrian rights, and the court often ruled in favor of them.

The term “Jaywalking” was coined and used for the first time in the 1920s, intended as propaganda by automakers to shift blame for accidents from the cars onto the pedestrians. With an amassing wealth and influence, city governments began siding with cars, often utilizing police forces to enforce the right of way of cars.

Adding fuel to the growing movement for car-centered urban planning were international influences like the Swiss-French architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier.

[1] A 1921 flyer using the newly coined term “jaywalking” [2] In July of 1953, residents of Philadelphia took to the streets to rally for the installment of stop signs. Here, a group of protesters block an intersection. (image: Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia) [3] 1920s Government safety poster that scorns jaywalking. (image: National Safety Council/Library of Congress) [4] 1922 sketch of Corbusier’s “Plan Voisin” for Paris. His minimalistic and geometric style is one of the leading influences of modern architecture. (image: Fondation Le Corbusier) [5] The Lower East Side of Manhattan Island, Hester Street in 1914. (image: Maurice Branger/Roger Viollet/Getty Images) (Jane Kim)

America’s toxic relationship with automobiles

However, this pro-car bias makes the various problems difficult to recognize. A study led by a group of researchers in the United Kingdom explained, “The way we defined motonormativity in our paper was as a shared automatic assumption that travel is fundamentally a motor activity and must remain that way.”

Slowly but surely, this manufactured preference for automobiles arose in America, as well as other wealthy nations around the world. Soon enough, people’s pro-car biases became so strong that even obvious downsides of the car-takeover were easily dismissed. Presently, very few ever question the legitimacy of vehicles owning the streets.

Governments that promote electric vehicles (EVs) as opposed to other green forms of transportation clearly demonstrate this kind of pro-car bias. The push for EVs is certainly a positive sign for climate conscience policymaking; on the other hand, it doesn’t address the issue at its core — our addiction to cars.

A large range of issues

The world has turned a complacent eye to many obvious problems stemming from car dependence. Here are just a few.

Number one: our toxic relationship with motor vehicles is a source of public health concerns. According to Yale Climate Connections (YCC), “Car dependency is associated with ‘an epidemic of physical inactivity,’ … which significantly increases the risk of cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and strokes, among other health problems.” Car accidents are also the leading cause of death in the U.S. for Americans under the age of 55.

Number two: according to the UN, simply switching from driving to public transportation can cut an individual’s carbon emissions by as much as 2.2 tons each year.

Number three: highway constructions have historically and currently been proven to exhibit racial and socioeconomic biases. The Vermont Journal of Environmental Law (VJEL) stated, “Highways in urban areas were deliberately constructed directly through poor neighborhoods where citizens were under-resourced and unable to fight back against displacement.”

Number four: the high expenses. Not only has the average price of cars hit an all-time high in recent years, the typical U.S. household’s annual spending on transportation — mainly cars — are second only to the cost of housing. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) revealed that in 2019, the U.S. federal government spent $46 billion on highways alone.

On the flip side, alternative forms of transportation hold great potential. John Weldele, one of Foothill Technology High School’s (Foothill Tech) science teachers, has biked to work ever since he began his first teaching position. Weldele explained, “I get my exercise and leave the stress of the day behind as I’m getting home. It’s great for the environment, and I have to buy less gasoline, so it’s economically good for me. I really feel like… there’s no downsides to it.”

What are Foothill Tech’s takes?

Ventura, Calif. is a suburban beachtown that sprawls from sandy beaches to rumpled hillsides. It is a far cry from its blaring metropolis of a neighbor, Los Angeles; yet, just like any city, infrastructure and transportation remains high on its radar.

Residents are no stranger to rush hour traffic woes, and a fair number of Foothill Tech’s students have taken it upon themselves to turn to alternative forms of transportation. Notably, a rise in e-bikes has overtaken the community.

Baker Carlisle ‘26 has biked to school for the entirety of high school, and finds little qualms with the arrangement. He stated, “I feel perfectly safe biking to school — as safe as you would in a car, with all the chaos around school… It’s just easier than driving a lot of times because you don’t have to find parking.”

Weldele also added his own perspective. “I do feel safe. Some people might say it’s a misguided feeling, and I actually have been in accidents before, but it’s not really a concern of mine as I’m cycling.”

Ventura’s downtown, a relatively walkable area, is also a subject of interest. Although his main choice of transportation is his car, Nicholas Velasco ‘25 expressed desires for more pedestrian-friendly areas with blocked-off streets, similar to downtown.

Interestingly, the closure to cars of Ventura’s downtown in November 2021 (Main Street Moves) was one of the many cases of the urban revitalization movement sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic. With a need for more outdoor and socially-distanced options, many cities pursued initiatives for more pedestrian-friendly streets to encourage safe human interactions. However, the movement of the era made lasting impacts: the Ventura downtown decision was unanimously repeated in January of 2025, demonstrating both the city government’s continual commitment to a pedestrian-friendly downtown and city residents’ rapport.

Widening choices and perspectives

John F. Kennedy once said, “Our cities must be not only places where people live, but places where they live well.”

The declaration was significant then, and is perhaps even more appropriate for the policymakers of today. As successive waves of technological advancement carry humankind into the 21st century, it is imperative that communities remain grounded and connected.

Though cars will undoubtedly remain an essential part of transportation for years to come, it is clear that America’s over dependency upon them is toxic and self-destructive. However, combined with the aftermath of the pandemic and natural social changes like the rise of e-bikes, change is possible.

Cities can empower its residents with freedom in transportation by widening the range of alternative transportation available to the average person. This includes, but is not limited to: implementation of city bikes, public transit reform and streets that better integrate foot traffic. For long distance travel, federal infrastructure projects should focus on pursuing statewide and interstate rail systems for both people and cargo, minimizing carbon emissions and costs while maximizing land use efficiency and accessibility.

While car-centered approaches to urban planning have shaped U.S. cities for the past several decades, voices from younger generations demand for change: a greener, brighter, and more connected future.