Jason Messner

Teenagers can find drugs like opioids and marijuana to be easily accessible under their parents’ roofs.

Investigative: Is Foothill “where the grades are high and the students are higher?”

August 18, 2018

Editor’s Note: This article includes potentially upsetting discussion of drug addiction, fatal drug overdose and death caused by driving under the influence.

*Editor’s Note: Sources’ names that are accompanied by asterisks are altered names that were granted on conditions of anonymity. These sources agreed to discuss their personal relationships with illegal drug and alcohol consumption only on the condition that their names would be omitted or changed in the article. We have arbitrarily provided names for each anonymous source for clarity’s sake. More information on our anonymity policy can be found here.

“Foothill: where the grades are high and the students are higher” is a well-known phrase that’s commonly and light-heartedly exchanged by students at Foothill Technology High School (Foothill) and other Ventura Unified School District (Ventura Unified) schools.

What amount of truth does this phrase actually hold? Are students at Foothill intoxicated as often as they perceive themselves to be? Are they getting intoxicated to relax and relieve stress, or simply to have fun? And more importantly, how do they feel about their decisions? Do they regret taking certain drugs, or do they enjoy it and want more? Are students who choose to use drugs putting people’s lives—including their own—at risk?

Statistics provided by questionnaires like the California Healthy Kids Survey can provide limited insight to these questions.

Posed to spark thought, discussion and reflection on a personal level, here is the Foothill student perspective on teen drug use.

Party Culture: The Social Psychology

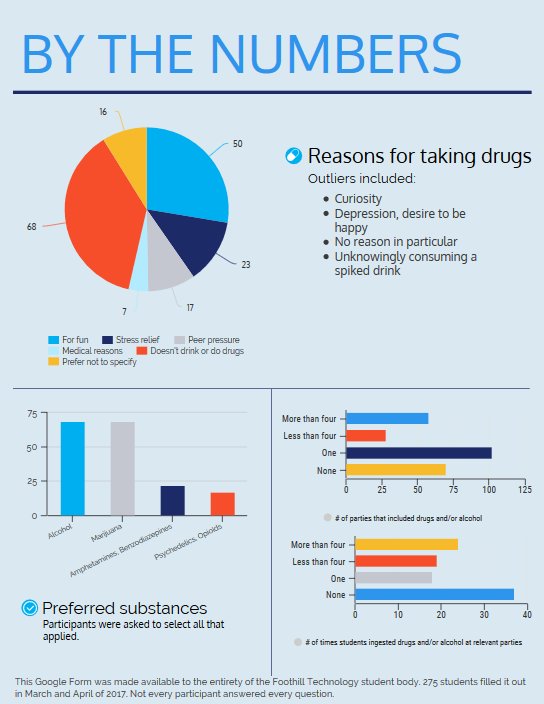

Drug use by the numbers: Foothill students’ party tendencies, substances of choice and reasons for drug use.

Ethan* ‘19 has thrown two parties and a total of five ‘kickbacks’ at his house. Over the years, Ethan’s house has been home to more than 30 parties. While a typical high school party is known for hosting large crowds, kickbacks tend to host an average of ten close-knit friends. With parties, there’s more music, more strangers, more friends, more games and more expenses. At kickbacks, “everybody pitches in for everything you need.”

Ethan describes the process of planning a party as “very easy.” He will post an invite on the social media platform of Snapchat or send out an exclusive invite to “x amount” of people. Then, he and his friends wait to see what sort of responses they garner, give more information to the guests and clean their home.

As far as the acquisition of alcohol goes, parties can advertise to “bring your own bottle/beer” (BYOB), or a small entrance fee at the door. The fee is not for profit, Ethan says, but to help get the events going.

Because he is not of legal drinking age, Ethan will give an older sibling money to buy alcohol for his parties. He will never buy any alcohol stronger than beer in an attempt to prevent teens from getting more intoxicated than they can handle. However, with policies like BYOB, it’s not difficult for high proof liquor to become abundant.

As far as the acquisition of marijuana and other drugs goes, Ethan contacts various people through social media to make purchases. Sometimes Ethan pays for the drugs alone; sometimes he has friends help him out.

In order to purchase the drugs, Ethan has to find a dealer: “It’s never been the same person for more than like three months ‘cause usually the person—they’ll stop selling, they’ll stop buying to sell or they’ll just kinda go lowkey and not advertise anything anymore.”

Ethan said that when he throws a party, the parent that he lives with “doesn’t care, fortunately enough.” His neighbors “keep to their own and we keep to our own.”

Ethan believes that parties are “a more comfortable environment” for teenagers to experiment with “whatever they wanna try.”

“The first party I ever went to—I felt comfortable,” he said. “I wasn’t scared of anybody; I wasn’t scared that anybody was gonna beat me up; I was just being myself, doing my thing.”

He said it “felt way better” than trying to hide intoxication from his parents at home or being out late somewhere where he shouldn’t be.

He furthered: “If you like it, you might go to a couple more parties; if they don’t like it, they’ll know. They’ll know that it’s just not for them, so they won’t continue [by] doing it by themselves or they won’t continue going to parties.”

Driving Under the Influence

The CDC reported that people aged 12-20 consume 11 percent of all alcohol in the United States; 90 percent of this drinking is classified as binge drinking.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2016, the blood alcohol concentration (BAC) was .08 percent or higher for 15 percent of drivers aged 15 to 20 who were involved in a fatal car crash. A 2015 CDC national survey revealed that in the preceding month, 20 percent of students had gotten into a car with a driver who had been drinking and 8 percent of students had gotten behind the wheel after drinking.

Driving under the influence is no stranger to Ventura Unified. In 2014, Former DeAnza Assistant Principal and Foothill teacher Christopher Prewitt passed away in 2014 after being hit by a driver who was under the influence. The Ventura County Office of Education’s Friday Night Live is a substance abuse prevention program that focuses on at-risk adolescents. Foothill’s Every 15 Minutes is dedicated to distracted driving prevention.

In accordance with the expectations, the student body reflects awareness taught in these programs and learned by personal experience.

Based on Connor’s* ‘18 experiences at parties and kickbacks, he felt confident to say that “everyone’s in unanimous decision that people shouldn’t drink and drive.”

He doesn’t see drinking and driving often, “if ever.” Most of the time he sees people rely on designated drivers (DDs), Ubers or their own two legs.

When Ethan hosts parties, he takes preventative steps to avoid these life-threatening situations by keeping tabs on his guests.

“I always ask who’s the DD between every group that walks in through my door,” Ethan said. “Not a single person gets by without me knowing who’s driving that person.”

If Ethan sees a DD drinking, he will turn to on-demand transportation companies like Lyft and Uber, or ask another sober person to help out with rides.

“I don’t think I’ve ever had anybody leave my house drunk and gotten into their car and drove themselves home,” he said. “If they did, I hope they didn’t get hurt and I didn’t know about it.”

The Appeal of Intoxication

Young adults can rely on substances to turn an otherwise normal night into a good time. Some teenagers will drink, smoke or ingest other substances with the intent of gaining confidence to do something they otherwise wouldn’t, like dance, make new friends, experience a sexual first or ‘hook up’ with someone they’re interested in. Others will do so to relax and decompress.

Ethan believes drinking or smoking at parties to be a good thing, as it can release “a little bit of that tension” that teenagers have.

“It’s almost like letting off some of that steam,” Ethan said. “Kids are curious. Teenagers wanna smoke, wanna drink—I mean regardless whether they do or not, they’re thinking about it at some point in their high school career, right?”

Jordan* ‘18 said that the types of drugs that he finds himself willing to take varies, depending on his mindset at any given moment. He has consumed amphetamines, benzodiazepines, cocaine, LSD, marijuana and MDMA; he ingests cocaine, LSD and marijuana more commonly than the others.

“Usually it’s the time you catch me in,” Jordan said. “It’s like, ‘Okay, I wouldn’t do that,’ but maybe the next week if I’m in a different mood—different place in my life, I’ll be like, ‘maybe I would do that.’”

Jordan’s varying mindset is determined by his overall mood and “care about the world.” He looks to see whether or not these factors have changed since his last consideration.

When he’s sober, Jordan feels “quite out of the picture,” as he doesn’t feel like he connects easily with people. When he’s under the influence, he feels happier and better, which makes him feel apart of his community.

In his life, Connor has tried alcohol, amphetamines, benzodiazepines, cannabidiol (CBD), lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), marijuana, methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), nicotine and opioids. He takes some more often than others.

He thinks that taking drugs or drinking alcohol is “nice from time to time” because it helps him break up the predictability and stability of his life. He enjoys seeing the world “from a different perspective.”

“Usually it’s the time you catch me in,” Jordan said. “It’s like, ‘Okay, I wouldn’t do that,’ but maybe the next week if I’m in a different mood—different place in my life, I’ll be like, ‘maybe I would do that.’”

“It’s not only the day that you take the drugs, but the days after that you see everything in a different light, and it’s kind of like expanding your sense of reality,” Connor said.

Ava* ‘18 has a similar take: “It gives you like an alternative reality for a second just so you can escape normal, everyday dumb s— that you don’t wanna deal with. I mean, it’s always an unhealthy escape, but it’s an escape.”

Ava does not mind too much the potential detriments to her health that certain drugs can cause.

“I don’t really care enough about myself because it gets me out of the mentality that I’m in every single day,” Ava said. “It’s worth it, I guess.”

Transcending Reality with Hallucinogens and Psychedelics

Ava sees herself as more likely to try psychedelics than other drugs. She likes the idea of the drugs helping her “unlock her brain” so that she can see the world in an unimaginably different way.

Similar to Ava, Connor prefers the trips of hallucinogens over the highs of other drugs: “They have the most value for teaching something about yourself and about, like, exploring the beauty of the world around you and just kind of understanding it.”

Well-read in research about psychedelics, Connor believes it to be a misunderstood umbrella of substances: “There’s been studies that prove to its effectiveness in treating PTSD, depression and disorders that haven’t been treated with other drugs before.”

Connor is right—studies are looking into benefits of psychedelics. The non-profit organization of MAPS (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies) has been conducting research that looks into the safety and effectiveness of therapy assisted by substances such as LSD, ayahuasca, ibogaine and MDMA. Researcher Jim Fadiman is conducting informal research on mood and energy boosts caused by routine LSD microdoses.

The “Smart Pills”

Other students find themselves taking medications that are commonly used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)—Adderall, Ritalin and Vyvanse—for an academic boost.

Prescribed Adderall XR as treatment for his ADHD, Connor could “get so much done so much more productively” while taking it in comparison to not taking it.

A 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health study showed that 119 million Americans above the age of 12 used prescription psychotherapeutic drugs in the past year. 15.9 percent of these users misused these drugs.

“It helped me focus, but it had negative effects on my personality, as far as dulling who I felt I was,” he said. “I didn’t crave social interaction anymore. I just wanted to be very secluded.”

“It’s not for everyone—it’s definitely changed lives and people take it every day,” Connor countered. “But for me, it changed who I was and I couldn’t keep taking it that way.”

Because of this, he stopped taking the pills daily as prescribed. He now takes it much more sporadically and in higher doses. He has moved from Adderall XR to Dexedrine to Vyvanse, trying to find the prescription that works best for him, but each have had their own negatives.

Madison* ‘19 used to take Adderall on a regular basis. Madison has ADHD, yet is not prescribed Adderall. When she doesn’t take it, she can barely get her schoolwork done. Her parents won’t let her obtain prescribed medication to treat ADHD.

She understands where they’re coming from in the sense that they aren’t entirely sure how medications can affect her developing brain, yet she does feel that she would benefit from a prescription. In fact, school was the main reason she started to take it, and seeing people her age take it too, she thought, “why not?”

“It’s upsetting because I feel like it would help me a lot,” she shared. “My parents aren’t open to it—I just can’t and because I’m a minor, I’m not allowed [to get it on my own].”

She recognizes that buying Adderall from someone else “probably isn’t the best” because the dosage was not approved for her by a doctor. The dosage seemed to be too high for her, giving her side effects that started interrupting her daily life.

She believes that at one point, she was addicted to it.

“In all honesty, what I’m doing—I don’t know if it is the best just because of how it makes me feel and I don’t know what it’s doing,” she shared. “It’s a bit reckless of me.”

“I stopped because I was realizing how depressed it was making me feel and how horrible I felt,” Madison said. “There was a time when I would just have migraines all the time because I wasn’t drinking water—I wasn’t eating and I couldn’t come to school. I was throwing up and I was constantly sick.”

When a Habit Turns into Something More

Connor became addicted to opioids when he was in the eighth grade.

“I found a bunch of Hydrocodone in my parents’ medicine cabinet,” he said. “Every Saturday, I would just take a dummy amount of Hydrocodone—norcos—probably up to 60 milligrams in a day.”

A fatal dose of Hydrocodone is approximately 90 milligrams per day.

He had one friend who knew about his habitual painkiller consumption, but he had joined Connor to take them. Other than that, no one else knew.

“He didn’t know to the extent of what I was using. He thought it was just time to time. That was not the case.”

He stopped taking the pills when he ran out.

“I had them at my disposal and I didn’t feel any negative detriments of them on my body at the time, so I was like, ‘okay, this is fine,’” he said. “If I wanted to buy them now, they’re super expensive so I just don’t even bother, and it’s not good for you.”

He is currently trying to regulate his use of any substance to one time per week, which is “maybe even pushing it.”

He always researches the drugs that he takes and consumes “moderate doses” that he is sure he won’t overdose on.

“He didn’t know to the extent of what I was using. He thought it was just time to time. That was not the case.”

He believes that “anything in moderation probably won’t cause much of any health detriment in the future,” but he would never touch drugs that are “highly addictive in nature” like heroin or methamphetamine because of “clear detriments” to his health that they pose.

The Multidimensional Impact of an Overdose

For the AP English & Composition final, students were asked to deliver speeches about an America that they hoped to grow old in. Kennedy Gomez ‘19 wrote hers about drug usage. She experienced firsthand how a loved one’s drug abuse can not only affect the user, but additionally his/her loved ones, those who love the user.

Gomez’s uncle recently passed away due to a drug overdose.

“He started out just smoking weed, and everyone thinks that that’s fine—harmless,” she shared. “This year, he transferred to heroin. He recently passed away from an intentional overdose.”

Her speech, in part, was inspired students joking that “the only thing higher than Foothill’s test scores are their students”—and how this works to trivialize the gravity of drug use.

“Right now, you might not think it’s a big negative impact because right now it’s just, ‘oh, it’s casual—it’s not affecting your life’, but one little thing can easily turn into a large […] thing.”

Drug Culture On and Around Campus

In the past couple of years, there’s been increasing talk of students under the influence while in class. Some do it for fun; others take amphetamines to enhance their academic performance.

Noelle Hayward ‘21 said that she doesn’t “feel the need to” do drugs, nor does she think that school should be the place to do so.

Ava thinks that the problem with a student being under the influence of drugs on campus lies deeper than its superficiality. To her, concerns about the individual should be raised more than they currently are.

“It’s not the fact that they have drugs on campus,” she said. “It’s a person that’s struggling, and they don’t necessarily know what to do because they’ve turned to drugs, and that’s easier than actually dealing with your problems.”

Connor thinks it’s “stupid” for students to get significantly high and then go to class: “it’s just a middle finger to the school system.”

“I mean, it’s their life—they decide what they’re doing,” he said. “But clearly, it’s not the most effective for trying to study or focus in class.”

“I think the reason people will do it at school is because they find it boring,” he continued. “But that’s not the school system’s fault; it’s just their own fault for not working hard enough.”

“Too ‘Juul’ For School”

In 2018 specifically, vape pens such as Juuls and Suorins have become increasingly popular. Resembling USB sticks, Juuls are rectangular, rechargeable, easy-to-conceal e-cigarettes. Some students utilize these pens on campus, in the bathroom or during class.

Although Juul claims to intend to keep their addictive nicotine products away from underage teens, high school students are still finding ways to get ahold of these e-cigarettes. The company is currently being sued for allegedly engaging in deceptive marketing of Juul as safe to teenagers.

Connor thinks that vaping in class has become more popular now because of the rise of Juul. He thinks that vaping the “discreet, small” Juul is far easier to get away with in comparison to a vape box mod, which produces “fog machine clouds.”

He thinks doing so during class or on campus is “highly unnecessary,” as “school shouldn’t be a place for drugs.”

Vape juice comes in fruity flavors such as mango and blue raspberry, which speculators say is a marketing tactic directed towards adolescents and teenagers.

Austin* ‘19, an owner of both a Suorin and a Juul, hasn’t seen much vaping in class at Foothill, which he attributes to the teachers’ hands-on teaching style for preventing this from being a possibility whatsoever. However, he does notice the presence of the e-cigarettes.

“I’ve noticed a couple of guys go in [the bathrooms] and come out kind of wonky—I’d say ‘domed’,” he shared.

When comparing vaping to smoking cigarettes, Austin thinks “it’s a lot easier; it’s a lot nicer; it’s cleaner—no tar or tobacco going into your lungs.”

“I don’t really like using actual drugs,” he said. “I don’t really consider nicotine as an actual drug; it’s just more of a relaxant.”

Noah* ‘19 will vape off of his friends’ devices “maybe once or twice a week” as he does not own his own vape pen, nor does he want to.

“I feel like if I had one, I would be using it everyday and just get addicted,” Noah explained.

“I don’t really like using actual drugs,” he said. “I don’t really consider nicotine as an actual drug; it’s just more of a relaxant.”

Noah thinks that a lot of the people who vape aren’t aware of the risks that the devices pose. He notices that teenagers are vaping in and out of school in attempts to be cool—or “get ‘clout,’” as he puts it. He believes that there are “very small amounts” of information about the hazards of e-cigarettes in district-mandated anti-smoking lessons.

Hayward, on the other hand, believes that these campaigns have impacted our community, specifically our generation.

“I think there’s basically a lot less people who smoke cigarettes,” Hayward said. “Definitely, teenagers definitely don’t see that as often in public anymore, so that’s definitely had a large impact on people, I think.”

Foothill in the District

When presented the phrase “Foothill is where the grades are high and the students are higher,” Connor laughed. He claims that even the “kids you wouldn’t expect” to do drugs or drink have tried something or another.

“Almost everybody I know in the senior class [of 2018] and even the lower classes has done drugs of some kind,” Connor expanded. “And they do them fairly frequently.”

“I’ve heard Foothill is the worst of the schools, but then looking at [other Ventura Unified] students, they seem crazier than us,” Connor said. “In my experience, Foothill kids have done more; like, most [other Ventura Unified] kids haven’t done molly or coke and stuff, but I’ve heard of a lot of Foothill students who have.”

“Everyone knows who you can get drugs from—who has access to specific kinds of stuff,” Ava said. “You can get drugs from so many people on campus that it’s just like—you just kinda know.”

“Almost everybody I know in the senior class [of 2018] and even the lower classes has done drugs of some kind,” Connor expanded. “And they do them fairly frequently.”

Jordan, on the other hand, doesn’t see the drug use as Foothill-specific: “I think it’s more teen culture in America.”

Hayward had yet to hear the phrase, and didn’t initially understand what it meant.

Gomez wrote her speech inspired by the seemingly light-hearted ‘joke.’

Madison believes that Foothill student body especially has created a reputation for drug use within the district. She also believes past graduating classes have shown a pattern of kids who typically enroll in Advanced Placement (AP) classes to be more likely to take drugs than those not enrolled.

“No one wants a really good school like Foothill to be looked at as a ‘druggie’ school,” she said. “[Other Ventura Unified schools] definitely get the bad rep, but if anything, most of the kids that I know who are dealers and do hardcore drugs—they’re all from Foothill.”

Madison doesn’t think that many people acknowledge this because she feels it goes largely unaddressed by both Foothill students and administration.

Where to go from here

Depending on the teen and the drug, some highs get better reputations than others, which encourages further use among a wider group of people. When taking any given substance, each teen’s intent, knowledge and concern for safety widely varies.

Some students find that they take hallucinogens to help them see the world in a new, positive light. They also want to erase the societal stigma that currently surrounds hallucinogens, and instead shine light on ongoing research that supports its mental health benefits. Students wish for amphetamine prescriptions to help get them on track in school. Others want to host people in their homes for comfortable, safe consumption of a desired substance.

Other students don’t believe nicotine to truly be a drug, and another doesn’t mind the health risks that drug use poses to her body because the highs are worth it. Another became addicted to opioids at 14 years old.

Some find the omnipresence of drug involvement among adolescents to be inherently worrisome. Other students seek to separate themselves from this pervasive drug culture while thinking no differently of peers who do choose to partake in drug use.

Do we need to increase the amount of substance abuse/awareness education directed at teens, or rather, should we focus on updating the classes to address new concerns in the spotlight? Should we begin talking about positive health benefits that substances like CBD, marijuana, LSD and MDMA can offer when consumed safely and in moderation? Or is there a concern that this will encourage teens to try these substances on their own?

How can we talk about drug addiction at Foothill in a way that is sensitive, personal and impactful? And should we? What would change if we were to tear down barriers and discuss these issues person-to-person, erasing confinement brought by labels like student-to-teacher, student-to-counselor or student-to-student?

Is it time to open the floodgates for personal, honest discussion and reflection between teens and adults about their relationships with drugs and alcohol? Or shall we continue with our regularly scheduled programming, and talk about teenage drug use on an impersonal level—only in class for a lesson or a generalized joke about an entire campus?

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Connor* was in the graduating class of 2021 instead of the graduating class of 2018.

Claire Dinkler • Aug 18, 2018 at 1:16 pm

SO THUROUGH I AM SO IMPRESSED

Vanessa Luna • Aug 18, 2018 at 9:10 am

This is an amazing and incredible article – one of the best articles to come from the Dragon Press.